How Chantal Akerman’s modernist masterpiece changed cinema

Alamy

AlamyJeanne Dielman came third in BBC Culture’s poll of the greatest films directed by women. It makes three hours of housework riveting, writes Nathalie Atkinson.

This story originally ran in November 2018.

Chantal Akerman’s drama – with the lengthy title Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels – premiered in the Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes in 1975, the same year Martin Scorsese’s Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore played in competition. It was Scorsese’s take on a widow with a son and her struggle for independence that was the commercial success: Jeanne Dielman did not even get a theatrical release in New York until 1983. But it was the Belgian film that was the bellwether of the era. In cinema, there is in many ways a ‘before’ and an ‘after’ Jeanne Dielman.

Read more about BBC Culture’s 100 greatest films directed by women:

- What the critics had to say about the top 25

- The full list of critics – and how they voted

“I was informed that I was a great filmmaker,” is how Akerman would later recall being mentioned by critics and scholars alongside Bernardo Bertolucci, Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Orson Welles at the age of 25, when her feature was hailed in Le Monde as “the first masterpiece of the feminine in the history of the cinema”.

Getty

GettyAnd now, Jeanne Dielman is number three in BBC Culture’s poll of the 100 greatest films directed by women. The film remains an influence and is a frequent subject of scholarly and critical analysis on aspects ranging from women’s social experience and gendered identities to cinematic form and psychoanalytic film theory.

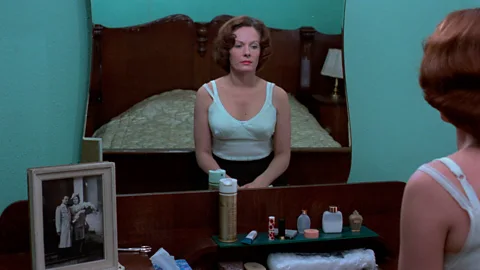

Delphine Seyrig plays an inscrutable widow in her forties who maintains a carefully circumscribed domestic routine around her modest Brussels apartment. Structured in three acts over three days leading up to her revolt in the final hour, most of Dielman’s time is spent keeping house for her indifferent teenage son (who does nothing for himself, not even turn on the radio). She earns money by entertaining a different man each day. Her daily client is greeted with brisk efficiency, serviced and dispatched in the time it takes to boil the dinner potatoes.

Alamy

AlamyFrom a fixed camera we observe the careful scrubbing of dishes and skin, the perfunctory making of a bed, the meticulous dredging of veal cutlets in flour (then egg, then bread crumbs) – all rote chores that if they were seen at all in other films would be elided into montage, but are here shown in their entirety. The observing becomes a sort of participation and because the tasks are trivial, the static long takes feel especially protracted. Critic Kathleen McHugh suggests that, in the relationship between its material and length, Akerman challenges the conventions of narrative cinema “in somewhat the same in which James Joyce’s Ulysses challenged those of the novel”.

Watching her chores in real time becomes a feat of mimetic endurance. Two hundred and one minutes long, Akerman’s domestic epic is not as extreme as Andy Warhol’s previous durational cinema, but its narrative subject and structure were radical in forcing viewers to experience the age of time. As the director and her star explained to a quizzical French presenter in 1976, the point was to make art of women doing dishes, thus “the length is also part of the commentary”.

Challenging conventions

After seeing Jeanne Dielman, scholar Marsha Kinder pronounced it “a very important film – a new step forward – not just for me, but for the history of film-making”. Jayne Loader, the American writer and director, may have been disappointed with the film’s “self-defeating” violent ending, but nonetheless felt it was deserving of serious consideration from both feminist and formalist critics. “The film raises further questions in of its contribution to the vital task of developing feminist art and feminist film language,” she wrote at the time, “providing a measure of how far we have come and what remains undone.”

Not that everyone appreciated Akerman’s genius. In her Cannes journal in Film Comment that year, for example, Mary Corliss disparaged the titular performance: “[Seyrig] proves that no one – not even an actress as enchanting as herself – can stoically knit, brew coffee and perform other tedious daily tasks for four hours without putting all but the most masochistic to sleep.” (For irony: the film is now taught in literature classes alongside readings of Madame Bovary to enhance understanding of histories and forms of feminine and feminist boredom.)

Getty

GettyIn Film Quarterly’s 2016 focus on Akerman, Laura Mulvey revisited the “unwavering and completely luminous adherence to a female perspective… embedded in the film itself”. Even its method of production was a landmark. To further challenge the male dominance of cinema, it was made with a mostly female crew (something like 80 per cent, rare even today), including cinematographer Babette Mangolte and editor Patricia Canino.

That perspective remains as much of an issue now as it was for Seyrig then. After playing the elegant haute bourgeoise for such directors as Alain Resnais, François Truffaut and Luis Buñuel for 15 years, Seyrig explained in an interview that she’d had enough. That led her to get involved in the 1970s women’s movement and, like many actresses today, she began to seek out female film-makers such as Akerman (and Marguerite Duras) in an effort to correct the way “theatre and films are very far from women’s consciousness about themselves”.

From the beginning, Akerman called Jeanne Dielman a love letter to her mother and insisted it wasn’t a film with a message. “When people ask me if I am a feminist film-maker, I reply I am a woman and I also make films.” Throughout her career, she resisted categorisation – structuralist, minimalist, feminist – yet finally itted: “Maybe [the labels] are right, but they are never right enough.”

How could any label be enough to cover Jeanne Dielman? The static long takes and atmospheric approach to auditory texture recall Solaris (Andrei Tarkovsky’s stark 1972 space meditation and another film landmark of that era). Pulitzer Prize-winning author Jhumpa Lahiri sees in it the traces of Edward Hopper and what it means to be alone. It is the architectural strategy of bodies and spaces in the cinematography of Gus Van Sant’s Last Days; it reverberates in the domestic bubble of Todd Haynes’s Safe; it spurred Sofia Coppola’s experiments with real-time in Somewhere; and its themes and form inspire similar exploration in recent foreign-language films The Chambermaid and Her Job.

Butterfly effect

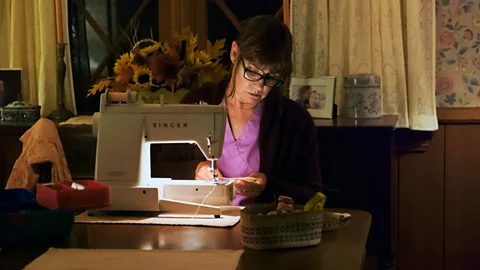

Kelly Reichardt watches it before starting any new project (see also: Meek’s Cutoff). Greta Gerwig is likewise enthusiastic; the director has talked about how watching Jeanne Dielman mesmerised her (“I almost felt like I didn’t blink”), and she included the take of the mother sewing in Lady Bird as an homage.

The sustained monotony of housework, a repetition Simone de Beauvoir likened to Sisyphean torture, should be stultifying viewing. But Akerman’s static long takes insist that we notice every hypnotic detail. The minimal dialogue underscores the sounds of routine that do break the silence – the chafe of a struck match, the breathy hiss of a gas flame, the rattle and thrum of the ascending elevator cage.

Alamy

AlamyBy the end of the film’s first painstaking hour, having closely followed her first typical day, we are so attuned to Dielman’s practised rhythms that on the second day we notice that something unusual has happened behind closed doors immediately, but only because of its butterfly effect. At first it’s a subtle arrhythmia – her coif is slightly dishevelled, the clack of her heels imperceptibly flustered. But the pace and disorientation increase, dinner is late, and even her son senses something is off. A minor disruption like a missed button becomes an unlikely source of suspense, pulling Dielman and viewer alike towards inexorable chaos. It’s riveting.

Read more about BBC Culture’s 100 greatest films directed by women:

- What the critics had to say about the top 25

- The full list of critics – and how they voted

How many of the films have you seen? Let us know using the hashtag #100FilmsByWomen.

Love film? BBC Culture Film Club on Facebook, a community for film fanatics all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.