The 25 greatest films directed by women

Alamy

AlamyCritics from around the world have their say on why these films have made it to the top.

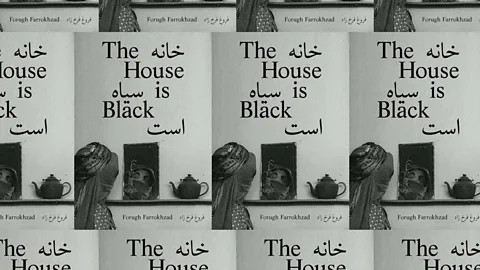

The House is Black

The House is BlackThe House is Black (Forugh Farrokhzad, 1963)

In 1962, at the age of 27, Forough Farrokhzad was already a notable figure in pre-Revolution Tehran and its bohemian arts scene. A poet on the rise, with some experience as an assistant director and an editor at the Golestan Film Unit, she was commissioned to shoot a documentary in a leper colony in north-western Iran. Filmed with a modest crew over two weeks, The House Is Black is Farrokhzad’s cinematic legacy, having died in a car crash at 32.

A poem built on molten flesh and rhythmic montage, this pulsating 22-minute short can also be seen as a political allegory for society as a whole, yet Farrokhzad frames her subjects’ everyday life with subtle comion. Her voiceover propels beyond the physicality, even beyond the medium itself. Music and dance rhyme with clinical routine; prayers embrace children’s games and domestic gestures. Nothing is mundane here, including the filmmaker’s decision to adopt one of the children from the colony.

Yoana Pavlova, founding editor of Festivalists.com, Bulgaria

Alamy

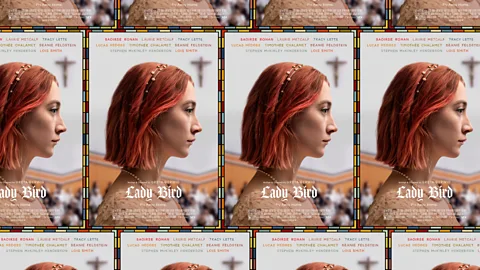

AlamyLady Bird (Greta Gerwig, 2017)

Born in 1988, I spent my formative years listening to Nine Inch Nails (and secretly sobbing to Justin Timberlake) and playing Snake on my Nokia. It was the best of times, it was the most embarrassing of times. Greta Gerwig is perhaps the first filmmaker to capture the bitter nostalgia my generation feels towards the early 2000s. Lady Bird, set in Sacramento between the autumn of 2002 and the summer of 2003, is a love letter to growing up, trying on adult outfits and self-importance in spite of knowing very little about anything. The protagonist is an old soul yearning for uniqueness in a conformist Catholic school, played with wide-eyed naiveté by Saoirse Ronan. But the film is also a story about parenthood, raising children and letting go. It starts with Lady Bird and her mother (the divine Laurie Metcalf) lying in bed, and then shows how this symbiotic state is no more. Seldom have I seen such an engrossing and moving portrayal of a mother-daughter relationship on screen.

Anton Vanha-Majamaa, freelance film writer, Finland

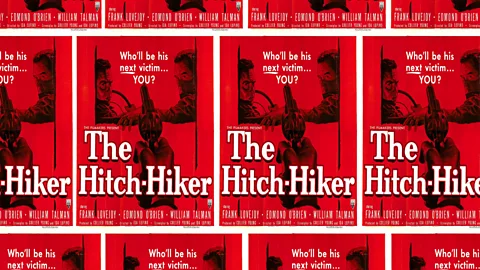

The Hitch-Hiker

The Hitch-HikerThe Hitch-Hiker (Ida Lupino, 1953)

As captivating and thought-provoking as any of the best examples of film noir, Ida Lupino’s The Hitch-Hiker deserves recognition among the best movies of the genre, beyond being considered the only film noir directed in Hollywood by a woman. Ida Lupino – the first female director to be part of the studio system in Hollywood, an already outstanding achievement by any standard – proves as masterful as any other director from the era with this, her finest film.

Stripped down to its bare essentials as a road movie, The Hitch-Hiker is a profound and dark character study about a sociopath on the run, playing mind games with a pair of innocent captives.

The tension and suspense are centred on these three characters, steadily and relentlessly built through the dynamics inside a car, in mental battles of survival, in a multi-layered game of contrasts, in close-ups and conversation.

A trailblazing proposal for film noir, the film takes full advantage of the visual style of the genre in the inside-the-car shots and adds elements of suspense and the spirit of what would eventually be known as the serial killer movie. The film is a masterclass in narrative economy and precision that can only come from a filmmaker in absolute control of the cinematic language and at the top of her game. The power and intensity of Lupino’s The Hitch-Hiker remains as strong and captivating as it was more than 65 years ago when it was released.

Arturo Aguilar, freelance film critic, Mexico

Alamy

AlamyWe Need to Talk About Kevin (Lynne Ramsay, 2011)

An alarming sense of horror is present from the beginning of We Need to Talk About Kevin. Too soon, we begin to understand exactly why. The story unfolds in frantic cuts through past and present, while director Lynne Ramsay cleverly changes Tilda Swinton’s hair to avoid confusion of timelines. Swinton – in amazing form – is the colourful Eva who is dulled by motherhood and her difficult son. For the most part it’s easy to sympathise with her situation – but then her smallest actions and casual phrases irk and gnaw. Ramsay boldly dives into the impossible question: is Kevin evil because his mother doesn’t love him, or does she not love him because he is evil? There is no answer, only pain. As a viewer you are forced to reflect on what you would do if you were in Eva’s shoes. The film is beautiful, and so is a young Ezra Miller as teenaged-Kevin – but oh so cold. Just like he forever haunts Eva, this film will stay with you forever. It’s really not very pleasant – but we need it.

Ida Rud, freelance film writer, Denmark

Alamy

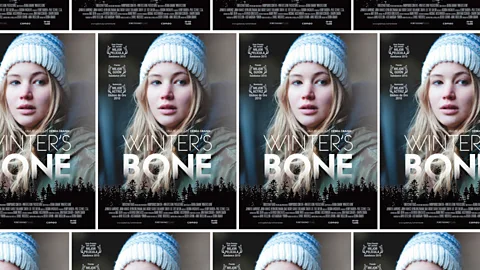

AlamyWinter’s Bone (Debra Granik, 2010)

There’s a reason Jennifer Lawrence was the obvious choice to play Katniss Everdeen in The Hunger Games. That reason was Winter’s Bone, Debra Granik’s terse, lyrical backwoods noir about a hard-bitten 17-year-old (Lawrence) who discovers she has less than a week to track down her bail-skipping father before her family are evicted from the home he’s selfishly put up as collateral. The rabbit-skinning resourcefulness of Lawrence’s character, Ree, certainly makes her performance feel like a real-world blueprint for her work on that aforementioned saga, but it’s also perfectly in sync with Granik’s empathetic, quietly subversive approach, which embeds us in the closed-off world of Missouri’s meth-ravaged Ozark Mountain region and proceeds to find the humanity and complexity in people traditionally portrayed in movies as hillbilly stereotypes or one-note villains or victims. The resulting film – which picked up four Oscar nominations – is both brilliant character study and tense thriller, with Granik’s foregrounding of women and insistence on naturalism subtly exposing the insidious nature of male violence so casually celebrated in the westerns and detective films with which Winter’s Bone shares some DNA.

Alistair Harkness, film critic, The Scotsman, UK

Alamy

AlamyClueless (Amy Heckerling, 1995)

It’s hard to praise Amy Heckerling’s Clueless without parroting its now iconic dialogue. The hyper-specific language, verbal and visual, of the teen comedy is a testament to its brilliance. Just say the title and phrases like ‘as if’ pop into your mouth while yellow plaid miniskirts and architectural hats cloud your vision. Heckerling took Jane Austen’s Emma and got rid of the Regency empire waist gowns, reimagining the meddling matchmaker as the queen of the Beverly Hills high school scene. Thus begat Alicia Silverstone’s Cher Horowitz, a mall-rat power negotiator. Cher, like almost all other characters in Clueless, is both archetype and subversion. She’s a ditz who really isn’t that ditzy at all; she’s a popular girl, who truly is altruistic, even if that altruism is sometimes misguided. Heckerling created a fantasy in primary colours that seems entirely of its era and timeless. It goes without saying that Clueless is a total Baldwin of a movie, and not at all a Monet. Unlike the painting, it gets better the closer you look at it.

Esther Zuckerman, senior entertainment writer, Thrillist, US

Alamy

AlamyOrlando (Sally Potter, 1992)

There are moments in Orlando, Sally Potter’s magnificent second feature film, that still provoke gasps today. Re-watching it recently, I was again captivated by a fresh-faced young nobleman (the title character played by Tilda Swinton) blessed with eternal youth by a fading older monarch (Quentin Crisp as Elizabeth I). “Do not fade. Do not wither. Do not grow old,” the dying Queen dramatically instructs.

The film’s epic timeline spans nearly 400 years, and there is something beguiling and deeply lasting about Tilda Swinton’s now-iconic early-career performance as both a man and a woman in the very same role.

It feels too simplistic, by 2019 standards, to celebrate Sally Potter’s empowering Orlando as simply a ‘gender-bending’ tale, because in many ways this story is finally, fully revealed today. Its fluid character is liberatingly not looking to be defined by a narrow, binary label, and that’s a radically hopeful proposition to witness.

Adapted by Potter from the 1928 Virginia Woolf novel written to her lover, writer Vita Sackville-West, Orlando is a movie that many will be talking about – discovering or rediscovering – in the coming months. The 2020 Met Gala, the famed annual fundraising event for New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute, and following exhibition, will be themed About Time: Fashion and Duration, and was specifically inspired by Potter’s film.

Eugene Hernandez, deputy director of film at Lincoln Center and co-publisher, Film Comment, US

Alamy

AlamyAmerican Psycho (Mary Harron, 2000)

At first glance a biting satire about the yuppies of Wall Street in the late 1980s, Canadian director Mary Harron’s American Psycho is a timeless masterpiece about greed and the loss of one’s sense of identity, as well as an excellent showcase of the power of the female gaze on the underbelly of male vanity and violence. Based on a novel by Bret Easton Ellis, Harron’s decision to cut out the elements of Penthouse-like male fantasy of the original, and instead bring a sense of reality, makes the blade of her satire even sharper. While Patrick Bateman (delectably performed by a pre-Batman Christian Bale) acts out sexual fantasies and goes on a murderous rampage, audiences are torn as we inwardly recoil in horror but also laugh out loud – not just at the mundane manner of his killings, but also at the recognition of aspects of our own greed. Whether or not one gets the contemporary references to 80s easy listening, this slasher-horror laced with comedy generates intense debate to this day, especially in of its ambiguous ending. With characters that are recognisable in all societies of the world, it’s hard to imagine any director eclipsing such a satire.

Nemo Kim, film critic and lecturer at Soon Chun Hyang University, South Korea

Seven Beauties

Seven BeautiesSeven Beauties (Lina Wertmüller, 1975)

Seven Beauties will always be known as the film that made Lena Wertmüller the first woman to ever be nominated for best director at the Oscars. This is an impressive accomplishment by any means (which has happened merely four times since), but the film itself is even bigger than that. It is a riveting masterpiece, so bold and provocative in its depiction of humanity that it could never be made today.

From the satirical opening accompanied by a deadpan poem, all the way to one of the most powerful and well-constructed ending shots in history, Wertmüller found countless ingenious ways to film monstrosities without letting us take our eyes off the screen.

Based on her own original screenplay, she walks us through the turbulence of Italy in the first half of the 20th Century, embodied in Pasqualino, a charming yet damaged man who sets out on a journey to the lowest places of the human soul. As beautiful as it is shocking, poisonous yet merciful, Wertmüller’s 10th feature film is an explosion of cinema, as much of a punch to the guts now as it was 44 years ago.

Orr Sigoli, freelance film writer, Israel

Alamy

AlamyWanda (Barbara Loden, 1970)

Recalling Machiavelli’s The Prince, Barbara Loden set out to make a useful film for us to subvert the patriarchal power structures in which we live. But Wanda showed how such a subversion wasn’t possible, instead staging an imagined version of it. Surely, Loden would have agreed with Gilles Deleuze’s maxim “it’s by banging your head on the wall that you find a way through”. She turned the screen into a wall of impossibilities by inventing a new use of the long shot, and throughout the first – and only – feature film she made, the long shots never show things in perspective despite their wideness of view. Rather, they are systematically given as plane deserts, in which the title character, played by the writer-director herself, is condemned to exist as a mere ‘floater’, deprived of the ability to act on her surroundings.

Jun Fujita Hirose, author of Cine-capital, Japan

La Cienaga

La CienagaThe Swamp (Lucrecia Martel, 2001)

The metal-scraping sound of chairs being dragged across concrete. An ice cube clinking in a glass of wine. A drunken and shaky hand, filling it. And beyond, a big storm climbing up Salta’s mountains, ready to leap into the valley. It’s surprising how many of Lucrecia Martel’s iconic sounds and images appear in the opening of The Swamp (her feature-length debut), set to penetrate the collective unconscious of Argentina’s cinematic lanscape. The story of bitter rivalry between three families serves as a large-scale fresco of Latin America’s class and race relations, aristocratic decadence and the power of myths. However, what could be just another social drama turns up to be something different, with a weirder, sometimes almost Lynchian undertone, the one of an enclosed world where everything is more mixed up than it seems: cousins having siestas in the same bed, the maids dismissing the bosses’ calls and the weight of several incestuous relationships festering in the families like the water in the opening scene’s pool. Martel has said that she sees the world as a pool: we are all floating in the same liquid, where infection remains one of humanity’s primal forces. The Swamp was the diving board, where we dived into this human broth.

Agustin Acevedo Kanopa, film critic for La Diaria, Uruguay

Alamy

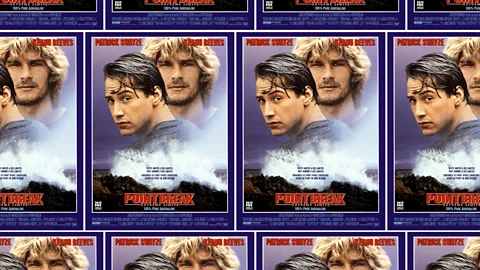

AlamyPoint Break (Kathryn Bigelow, 1991)

Shot by Kathryn Bigelow in the warm golden light of Los Angeles, 1991’s Point Break is a cop’n’surf classic (in fact, the only classic cop’n’surf movie made to date). From the twin irresistibility of blank-but-beautiful Keanu Reeves and a lion-maned Patrick Swayze surfing the waves, to Johnny Utah pumping out bullets to the sky because his bromance with Bodhi has gone too deep for Utah to shoot him, its best moments have ed into movie legend.

Point Break adds to the myth of Los Angeles as an endless summer city, where even crime is fuelled by the desire of its beautiful perpetrators to keep surfing the perfect wave. And waves of nostalgia will wash over modern audiences, too, watching it now; it speaks of a far more innocent time – the Cold War was over and the Ex-Presidents go robbing in Nixon and Reagan masks to a soft metal soundtrack. 9/11 was a whole decade away.

With the ease and style with which she made Point Break, Bigelow showed that she could make an action blockbuster as well as any male director. When she got her Oscar for The Hurt Locker, fans of this film know it deserves to be in the body of work she was rewarded for.

Emma Jones, culture journalist and critic, UK

Alamy

AlamyVagabond (Agnès Varda, 1985)

Despite being one of the great films of the French New Wave, Agnès Varda’s film Vagabond isn’t as well-known as the films of her contemporaries. The film follows the story of a young woman found frozen to death in a countryside ditch, the case of which is investigated by the director through fictional interviews and a subsequent reconstruction. Great films often leave some unresolved mystery at their core, an unknowable reality, and this strategy – narrative as fictional reconstruction – suits it irably.

Mona (Sandrine Bonnaire) worked as a secretary but grew tired of her work, setting off in search of freedom with a few possessions in a knapsack. What is striking about Vagabond is its sense of how impossible it is to live ‘randomly’. Mona is just a normal person; the film isn’t so much about her as the difficulty of shaking off civilisation. It follows the descent of a nonconformist individual seeking freedom into emptiness, vagrancy and, finally, death – suggesting how we have been so domesticated by civilisation that true freedom can only be death.

MK Raghavendra, freelance film writer, India

Alamy

AlamyZero Dark Thirty (Kathryn Bigelow, 2012)

Following her Academy Award wins for The Hurt Locker, Kathryn Bigelow delved into the hunt for Osama Bin Laden in her next feature. At first, this thriller of a ride, which takes the audience along with the special forces and CIA operatives who finally captured and killed the arch-enemy of the US, seemed poised to win big once again at the Oscars, but the film became embroiled in a political fight. One Oscar voter called for a boycott, claiming it “condones torture”, and the film was almost completely snubbed come awards season. What made this film such a polarising work of art? In no small part, Bigelow’s ability to tell a riveting tale while colouring her films with shades of human faults and hyper-realistic emotions – all wrapped up in a movie that tells it like it is, even if the story isn’t a pleasant one to tell. Jessica Chastain gives a riveting performance as Maya, a fictional character based on a composite of women who helped find and capture Bin Laden.

E Nina Rothe, freelance film writer, Italy

The Ascent

The AscentThe Ascent (Larisa Shepitko, 1977)

The first time I watched The Ascent, I felt like I was time travelling; I felt the snow, the pain, the cold, the blood, and the suspense. The scene where two soldiers, Sotnikov and Rybak, hide in the attic from the Germans uses camera angles and framing to such great effect that it’s almost too intense. The conflict between the two soldiers carries the story beyond heroism, war, and honour: the angelic look of Sotnikov and the treacherous Rybak’s betrayal…

Yet Rybak might not be the Judas the film suggests: I think he is a human stuck in a horrible reality within the limitations of his own personality. The Ascent is also a true artwork that balances perfectly unsettling anxiety and calming spirituality, with the viewer immediately entering the minds of the characters. It’s so unfortunate that The Ascent was Larisa Shepitko’s last (and best) film. Whenever I watch a Russian film, I her and ask myself the same question: what would New Era Soviet cinema be like with her still directing?

Tugce Madayanti Dizici, BirGün Newspaper, Turkey

Alamy

AlamyDaughters of the Dust (Julie Dash, 1991)

Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust is a spellbinding gesamtkunstwerk celebrating Gullah culture through the Peazant family’s final shared moments ahead of a planned migration to the north from St Helena Island, South Carolina. A multisensory ode to culture and memory, it is a collage of poetic poses that frames the characters (descendants of slaves settled in the Sea Islands) against astounding backdrops of sand, sea, sky, song and lush scenery. Even in silence, they appear in tune with an unheard symphony that incorporates the film’s unborn child – a metaphor for the Peazant’s hopes and uncertainties.

Embodying the griot (West African storyteller) in message and medium, Daughters of the Dust evokes nostalgia while simultaneously grounding the Gullahs’ daily routine. Like the film’s three generations of independent Geechee women, Dash is an emissary and a custodian masterfully guiding her audience across time.

Here, memory is in character as blessing and burden, a component and complement of the Gullah; the link not to be broken despite prevailing odds. Herein also lies the reality that memory, if not adequately recorded, may be left behind in pursuit of ‘progress’ as distinct cultures disappear into the anonymous uniformity of urban ambitions. A timeless and universal conflict that rings true beyond the Sea Islands.

Aderinsola Ajao, freelance journalist and film programmer, Nigeria

Alamy

AlamyFish Tank (Andrea Arnold, 2009)

Fish Tank, winner of the Cannes Film Festival Jury Prize, continues and goes beyond the strong tradition of British social realism. In her second feature film, Andrea Arnold follows the mood and style of her Oscar-winning short Wasp. The main heroine of her authentic and poetic drama set in an Essex estate is an angry teenage girl and would-be dancer, Mia (compelling newcomer Katie Jarvis), looking for a crack in the aquarium of her frustrating life. Mia’s desires connect with her mother’s new boyfriend (Michael Fassbender) will prove naive. Life doesn’t work out like it’s shown on television. Mia’s happy ending doesn’t look like a definite triumph, but only suggests a redeemed wisdom, a quiet short reconciliation – and the hope that if she could let go, like a balloon hovering over a housing estate, she might have a favourable wind.

Iva Přivřelová, freelance film writer, Czech Republic

Alamy

AlamyToni Erdmann (Maren Ade, 2016)

Toni Erdmann tells us about everyday conflicts among so-called ordinary people in all those routine situations that we pay no attention to. It is a story about the degrading of the importance of family in our fast-moving neoliberal world. It could all turn into drama, even a thriller, but Maren Ade gives us an intelligent and dynamic bitter-sweet comedy. And we laugh.

Dubravka Lakic, film critic, Politika, Serbia

Alamy

AlamyThe Hurt Locker (Kathryn Bigelow, 2008)

What makes The Hurt Locker so great? Is it the arrival of a bona fide movie star in Jeremy Renner? Or is it the whack-a-mole casting of world-class character actors Guy Pearce, David Morse, and Ralph Fiennes? Could it be its David v Goliath win over Avatar at the 2010 Academy Awards? Or perhaps the ceiling-shattering moment of Kathyrn Bigelow being the first woman to ever win best director (over her ex-husband James Cameron no less!). The truth, I think, is more simple: The Hurt Locker does what all great films do – it transports us. Bigelow puts us in the boots (and blast helmet) of a character whose journey couldn’t be further from our own, and then uses her superlative filmmaking skills to make us walk, hand in hand, through hell with him. By the time Renner’s sergeant William James sets off into the arid sunset, we are happy to part company with him, not because he’s a loose cannon (he is), but because our nerves couldn’t possibly withstand another of Bigelow’s air-tight action sequences. Films have taught us that war is hell, but it has never been this tense.

Adam Ross, chairman of Australian Film Critics Association, Australia

Daisies

DaisiesDaisies (Věra Chytilová, 1966)

Herbert Eagle, a film professor specialising in Eastern European cinema, once wrote that when the films of Věra Chytilová became available to a wider audience, Daisies would be regarded as a masterpiece. Eagle has been proven right, but it was a long time coming. Even though Chytilová’s feature-length debut from 1966 was hailed by Jacques Rivette – and was an influence on his own Céline and Julie Go Boating (1974) – Daisies remained in a cult film-ghetto and mainly screened at feminist festivals.

Daisies might be seen as harmless fun now; and fun it is, with all the jazz-dancing, slapstick and food fights. But in communist Czechoslovakia, the anarchistic escapades of the two female protagonists were scandalous. Marie and Marie are portrayed as ‘dolls’ who revolt and wreak havoc on institutionalised gender roles and consumer culture.

Today it is clear that Daisies, a collaborative effort of the finest artists in the Czechoslovak New Wave, with avant-garde montages, beautiful set design and superb photography, was among the best films to come out of that decade. The communist censors labelled Daisies as ‘depicting the wanton’ – and it still hasn’t lost a sliver of that delightful wantonness.

Hynek Pallas, freelance film critic, Sweden

Alamy

AlamyLost in Translation (Sofia Coppola, 2003)

Sofia Coppola masterfully portrays multiple levels of contemporary disorientation in this movie shot in Tokyo, and released in 2003. At one level, a middle-aged man becomes aware of the weak and dull link he has with his wife, after 25 years of marriage, while a young woman who has been married for two years finds herself alone, unable to recognise who she has married, and confused about her professional future. Moreover, both characters – ably performed by Bill Murray and Scarlett Johansson – show their confusion and haziness when confronted by a different cultural environment and language.

Coppola depicts them trying to enjoy the Japanese fusion of tradition, post-modernity, technology and escapism. But the escape seems to lead to nothing at the end of the day.

Murray plays Bob, a renowned but faded actor who is filming a commercial in Tokyo. He meets Charlotte (Johansson) in the luxury hotel where she is staying while her husband is away, working. Over conversations about life, marriage, work and children, the two develop a sincere connection – a kind of friendship. The Tokyo lights and streets reflected beautifully on the hotel windows are one of the signatures of this film.

Jacqueline Fowks, El Pais, Peru

Alamy

AlamyBeau Travail (Claire Denis, 1999)

Composed of the memories of a disgraced Foreign Legion officer reminiscing about his days in a Djibouti training camp, Claire Denis’ Beau Travail has the structure and feeling of a fevered dream. As narration from the melancholic Galoup (the inimitable Denis Lavant) softly guides us through the thin plot, it also opens up the film’s images of soldiers exercising under the hot African sun to other suggestive meanings: is Galoup truly entertaining a special relationship with the commander (Michel Subor), and is the new, handsome recruit Sentain (Grégoire Colin) threatening it? In this ambiguous space, where the subjectivity of man meets the harsh reality of the African desert, lies all the beauty of Beau Travail. Denis and cinematographer Agnès Godard bring out the sensuality of men’s bodies in images which, coupled with Galoup’s wistful words, gain a visceral urgency: we hold on to those glimpses of beauty like Galoup to his commander. Yet what elevates Denis’ film to the status of masterpiece isn’t its visceral power, but its clear-sightedness and unsentimental quality, which amount to veritable courage: though Galoup’s infatuation was a seductive fantasy, it was deadly, and the way Beau Travail highlights the limits and perishability of bodies prefigures Denis’ 2001 body-horror love story Trouble Every Day.

Elena Lazic, freelance film writer, UK

Alamy

AlamyJeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (Chantal Akerman, 1975)

Revolutions happen in real time sometimes. There’s something revolutionary about watching a woman in a sky-blue housecoat peeling potatoes at her kitchen table, dusting her house, searching for a missing button or brewing a pot of coffee. She does this almost silently, in long, static takes that stretch out over three gripping hours. The minutiae of everyday life, the stuff most filmmakers skip over or leave out, are central to Chantal Akerman’s 1975 masterpiece Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels; a hypnotising study of repression, anxiety, drudgery and time. Akerman, just 25 when she made the film, called these scenes “the images between images”. We in the audience sit waiting for something dramatic to happen, slowly realising that it has already happened; it is happening.

As we move through these domestic spaces, from kitchen to bathroom to bedroom, there are hints and suggestions that Jeanne (the wondrously contained Delphine Seyrig) is a sex worker whose apartment is also her workplace. The familiar takes on a strange cast. Things start to unravel, almost imperceptibly. Her assiduous cleaning, her meticulous daily routines, take on a new, darker meaning. Unease gathers until it ends in a burst of shocking violence.

Jeanne Dielman works like a time bomb; its slow-burning fuse sparking unnoticed under our feet. We can sense the blast before it happens, flinch as the shockwave es over our heads, and know the uprising has started.

John Maguire, film critic, Sunday Business Post, Ireland

Alamy

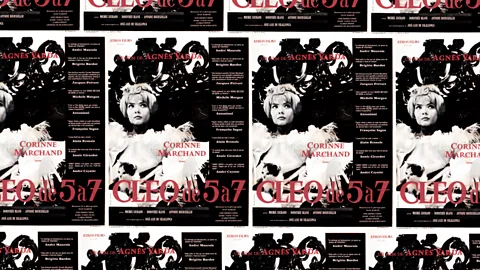

AlamyCléo from 5 to 7 (Agnès Varda, 1962)

Seven years after having been at the forefront of the New Wave with La Pointe Courte, Agnès Varda gave the great movement of modern French cinema one of its masterpieces. Following, in real time, a young singer as she waits for a potentially tragic medical diagnosis, the two-hour film offers an extraordinary circulation through reality, emotions and the pleasures of life. Alongside the magnificent Corinne Marchand, Varda walks the streets of Paris, filming with the attention to detail of a great documentary filmmaker. She sneaks into an apartment that becomes the setting for a mini-musical with composer Michel Legrand, celebrates the freedom of the female body with Cleo’s model friend and gives way to burlesque cinema with a silent short film starring Jean-Luc Godard and Anna Karina. During this encounter full of charm and sweetness, the shadow of the Algerian War looms, with Cleo meeting a soldier who is about to leave for the front. This modern though apparently modest odyssey is a hymn to life that never forgets the fatal horizon on which it takes place, mobilising a constantly inventive, feminist and sensual form.

Jean-Michel Frodon, film critic, Slate.fr,

Alamy

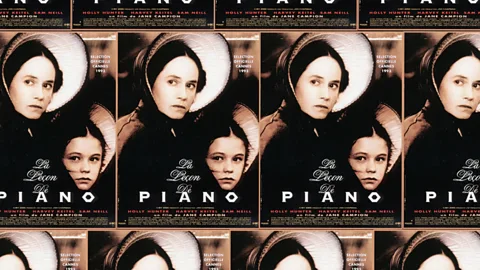

AlamyThe Piano (Jane Campion, 1993)

In writer-director Jane Campion’s Gothic romance and ecstatic monument to the female gaze, a mute Scottish woman named Ada is shipped to 1850s New Zealand to marry a stranger. Once landed, she is separated from her piano, her main instrument of communication. “The piano is mine,” she scribbles to her new husband, who has thoughtlessly sold it to a neighbour. This ownership is everything to Ada, because for all intents and purposes she is the property of others: the man who bought her for his bride; the daughter who demands her absolute attention and affection; the neighbour who barters piano keys for her body. From the scrutiny of a quarter-century removed, The Piano’s sexual politics and artless depiction of indigenous people have aged uncomfortably. And yet, the film has lost none of its potency – not in despite of, but because of, its unruliness. Two more legacies, both bittersweet: in 1993, Campion became the first – and to this day, sole – female filmmaker to win the Palme d’Or at Cannes, while Holly Hunter won the Oscar for her titanic performance as the tiny, steely Ada, only for her future leading roles to dry up.

Kimberley Jones, editor in chief, The Austin Chronicle, US