Wong Kar-wai: The master of ‘Hollywood East’

Alamy

AlamyHong Kong director Wong Kar-wai made three of the 100 greatest foreign-language films in BBC Culture’s poll. His unique style and universal human themes mark him apart from his peers, writes Vivienne Chow.

The cinema of Hong Kong, once dubbed ‘Hollywood East’, spans over a century and has been home to several great film-makers. But there’s only one name that made it on to BBC Culture’s poll of the 100 greatest foreign-language films: Wong Kar-wai.

Read more about BBC Culture’s 100 greatest foreign-language films:

- The 100 greatest foreign-language films

- What the critics had to say about the top 25

- The full list of critics who participated – and how they voted

Three of Wong’s films are on the list: Happy Together (1997) at 71, Chungking Express (1994) at 56 and In the Mood for Love (2000) at nine, (it also came second in BBC Culture’s 2016 poll of the 100 Greatest Films of the 21st Century). The 209 participating critics from 43 countries decided that despite the long lineage of Hong Kong cinema, Wong is one of, if not the only, Hong Kong film-maker to succeed in crafting a cinematic oeuvre that transcends the boundaries of language and culture.

Hong Kong has been a central character of several of Wong’s films. But what sets him apart from his peers is that he looks at the city with an outsider’s lens. Speaking to Laurent Tirard in Moviemakers’ Master Class: Private Lessons from the World’s Foremost Directors (2002), he described himself not as a director, but "an audience member who stepped behind a camera". Unlike other film-makers who immersed themselves within the city of Hong Kong, such as Johnnie To and Stephen Chow, the distance in Wong’s films allowed him to create a mesmerising, enigmatic cinematic world.

Getty

GettyBorn in 1958 in Shanghai, Wong moved to Hong Kong with his parents at the age of five. Unable to speak Cantonese, the local language of Hong Kong, the young Wong had trouble communicating with people, let alone making friends. It was the same for his mother, and cinema became the refuge for the migrant mother and son. “It was something that could be understood beyond words. It was a universal language based on images,” he told Tirard.

As a film enthusiast, Wong found himself at the right place at the right time. The New Wave of Hong Kong cinema began in 1979. Young directors with Western influences – such as Ann Hui, Tsui Hark and Patrick Tam – began making films that distinguished their work from mainstream studio productions by the likes of the Shaw Brothers and Golden Harvest. Wong’s journey to become a film director began at this point. After graduating from Hong Kong Polytechnic with a degree in graphic design, he signed up for the scriptwriter training scheme at local broadcaster TVB in 1981. A year later, he began writing scripts for films, which included Final Victory (1987) directed by Patrick Tam; the script earned him a nomination at the seventh Hong Kong Film Awards.

Getty

GettyWong put the visual sensibility he had developed as a child into good use when he left the TV station to make his own films, at a time when the local film industry was at its peak. Two years after John Woo’s A Better Tomorrow, which made the gangster genre a box office hit, Wong made his directorial debut with As Tears Go By (1988), a subtle and yet highly stylised gangster piece about two young thugs, played by Andy Lau and Jacky Cheung.

As Tears Go By laid the foundation for Wong’s subsequent work. Rather than being plot-driven, Wong’s films told stories through images and mood. He took this a step further in Days of Being Wild (1990) – set in a reimagined 1960s Hong Kong. It starred an ensemble of the biggest stars at the time, including Leslie Cheung as a disillusioned playboy, with his lovers played by Maggie Cheung and Carina Lau.

Universal truths

Hong Kong was producing some 200 films a year in the early 1990s. It was only the wild success of the film industry that allowed Wong to pursue his less commercial approach to film-making. Days of Being Wild was a box-office disaster locally but its critical acclaim earned Wong the status of one of the leading figures of the time. Riding on the economic prosperity of the last decade of the colonial era, he found opportunities to explore and develop his unique approach to film-making. With the help of cinematographer Christopher Doyle and art director William Chang, Wong developed a unique visual language and aesthetic. Images come first in Wong’s films; even the dialogues and fragmented narratives appear as if they are snapshots of moments.

Alamy

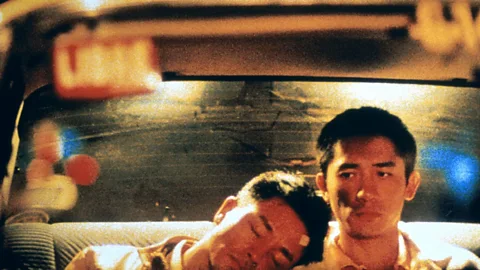

AlamyWong confessed to Tirard that scouting locations comes before writing, and he explores the idea of space – emotional as well as physical – in his films. Chungking Express charts in parallel spaces the quirky romantic adventures of two lonely Hong Kong policemen. Widely seen as a light-hearted offering, the film explores the complex themes of identity and anxiety as Hong Kong faced its anticipated handover. Buenos Aires is the exotic foreign stage for Happy Together, a gay love story trapped in a suffocating emotional space of repeated break-ups and reconciliations.

Whether they are set against the backdrop of the 1960s, a modern cityscape or historical times, Wong’s films have universal themes. One does not need a great depth of knowledge about the cultural and historical context of Hong Kong or Chinese culture in order to appreciate them. This is particularly true in Ashes of Time (1994). A critics’ favourite, it was an expensive production that took two years to complete. A subversion of the classic wuxia (martial arts) genre, it is essentially about ing and forgetting, a theme that can be understood regardless of one’s cultural background.

Alamy

AlamyBy the mid-90s, Wong had established himself as one of the best film-makers in the region, with Chungking Express winning him all the top accolades at the Hong Kong Film Awards in 1995. The city’s film industry was still a thriving and lucrative business but it was apparent that Wong wanted a bigger arena. While John Woo had already begun his Hollywood career making action movies, Wong won the Fipresci prize at the Stockholm International Film Festival for Chungking Express. It also earned praise from Quentin Tarantino, who was said to have pulled the strings to ensure the film’s overseas distribution. Making a name on the international stage was possible, and going to Hollywood wasn’t the only way.

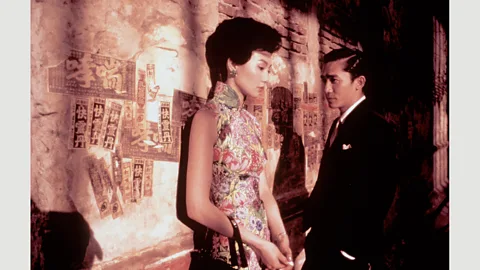

Happy Together arrived just before British rule over Hong Kong ended, and the city became the centre of global attention. The film sealed Wong’s star status, winning him best director at the Cannes Film Festival – the first Chinese person to receive the award. The early years after the handover remained largely prosperous, as if little about the city had changed, and 2000 saw the release of In The Mood for Love, a romantic drama set in 1960s Hong Kong that is widely recognised as Wong’s finest work.

Alamy

AlamyIn The Mood for Love ends in 1966, a watershed moment marking the beginning of China’s Cultural Revolution, and a year before the outbreak of the Hong Kong riots. The final scene has Tony Leung Chiu-wai’s character whispering his secrets into the tree hole, ing the vanished years. It marks the end of an era and the dawn of an unknown future, true in the film, as well as for Wong’s film-making and the fate of Hong Kong.

“In 10 years’ time the line between Hong Kong film-makers and Chinese film-makers will be very thin,” Wong told me in an interview in 2006. And his predictions came true. The post-handover era saw an abrupt change for Hong Kong’s film industry amid the astonishing growth of the mainland Chinese market, which was like a gold rush for many film-makers.

Alamy

AlamyWong was already ahead of his peers. Beijing Film Studio was one of the companies that produced Ashes of Time. The futuristic romantic tale 2046 (2004), a loose sequel to In the Mood for Love, had participation from Shanghai Film Group. And beyond mainland China, Wong ventured into the West, producing The Hand as part of the 2004 anthology Eros alongside Michelangelo Antonioni and Steven Soderbergh, and his first English-language feature My Blueberry Nights (2007), which starred Norah Jones, Jude Law and Natalie Portman.

“You learn many lessons, and what’s important is to find your audience instead of assuming there is one,” Wong told me. He found that audience with The Grandmasters (2013), a biopic of Bruce Lee’s master Ip Man that is an allegory of the world of Chinese martial arts. Starring Tony Leung Chiu-wai and Zhang Ziyi, it took Wong nearly a decade to complete and was his biggest commercial success to date. It was an epic film that managed to be true to its intentions while appealing to Chinese-speaking communities around the world. Some Hong Kong film-makers have been criticised for diluting the local character to appeal to the mainland. Ultimately, Wong is among the few who found fame despite never courting a particular audience.

“You don’t live for people, you live for yourself,” he said.

Read more about BBC Culture’s 100 greatest foreign-language films:

- The 100 greatest foreign-language films

- What the critics had to say about the top 25

- The full list of critics who participated – and how they voted

How many of these films have you seen? Let us know with the hashtag #WorldFilm100 on Facebook and Twitter.

Love film? BBC Culture Film Club on Facebook, a community for film fanatics all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.