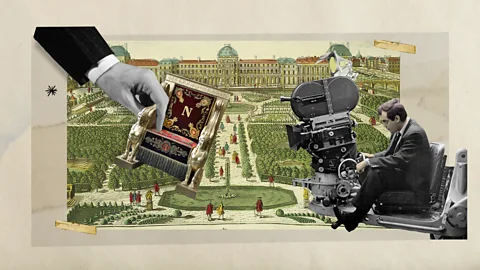

Was Napoleon the greatest film never made?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesStanley Kubrick’s biopic of Napoleon Bonaparte is regularly hailed by critics as the most tantalising unfinished picture of all time, writes Nicholas Barber.

The Stanley Kubrick exhibition at London’s Design Museum examines the making of every one of the extraordinary director’s films. But its opening section is devoted to a film he didn’t make: a biopic of Napoleon Bonaparte. As odd as that might seem, Kubrick fans are almost as fixated on Napoleon – to use its working title – as they are on anything else in his awe-inspiring canon. Critics regularly hail it as the greatest and most tantalising unfinished film of all. Besides, the story of how Napoleon was nearly-but-not-quite made exemplifies Kubrick’s sky-high ambition, his ravenous intellectual curiosity and his obsessive planning. “We put the display upfront because it’s a beautiful illustration of his process,” says Adrienne Groen, the co-curator of the Design Museum’s exhibition. “You can see his methods, and the amount of material he gathered before he even started.”

More like this:

This material consists of photographs, sketches, and documents, among them a gracious letter from Audrey Hepburn, turning down the role of Napoleon’s wife Joséphine de Beauharnais. (David Hemmings was the writer-director’s choice for the lead role.) There is a selection of Kubrick’s 276 books about the French emperor, including Felix Markham’s biography, which is illuminated with asterisks, underlinings and notes: “Who assassinated Tsar Paul? How did the politics really work?” Most intriguing of all is a wooden cabinet of index cards which Groen’s co-curator, Deyan Sudjic, calls “an analogue Wikipedia”. Pick any day in Napoleon’s life, pull open the appropriate drawer, flick to the corresponding index card, and there is information covering everything, says Sudjic, “from what he had for breakfast to what Josephine was wearing at dinner”.

But the Design Museum’s display represents just “a small fraction”, explains Groen, of Kubrick’s Napoleon collection. It was while he was completing his science-fiction masterpiece, 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), that he decided that his next subject would, in his words, be “one of those rare men who move history and mould the destiny of their own times and of generations to come”. He sent researchers all over Europe on Napoleon’s trail – and one of those researchers was his brother-in-law and long-time executive producer, Jan Harlan. “I was in Zurich in 1968 and 1969,” says Harlan, now aged 82, “looking for relevant material, books and drawings, simply everything I could find on the period from the French Revolution until The Congress of Vienna in 1815. Other people travelled for weeks through , and the UK on the same mission.” No detail was too small to fascinate Kubrick, whether it was the colour of the soil on a battlefield to the shape of a nail in a horseshoe. “He loved research and study,” says Harlan. “Pre-production and editing were his joy – filming itself a necessity.”

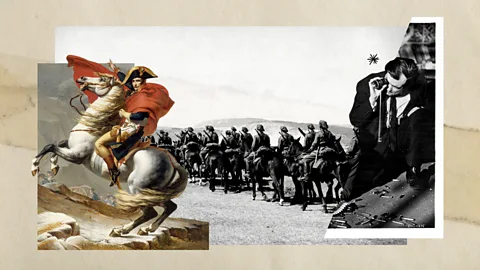

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn 1969, Kubrick crammed his research and study into a 148-page screenplay. As Harlan observes, “Stanley’s scripts were often very different from the final film,” but it’s clear that the biopic wouldn’t have confined itself to one part of Napoleon’s life, following him instead from his birth in Corsica in 1769 to his death on the remote island of Saint Helena in 1821. Its emphasis would be on the battles Kubrick called “vast lethal ballets”, as well as on Napoleon’s love for Josephine, “one of the great obsessional ions of all time”. Crucially, the film wouldn’t be a “dusty historic pageant”, but a painstakingly authentic evocation of life as it was lived in the 18th and 19th centuries. “The ideal,” says Harlan, “would have been to leave the audience feeling as if they had watched a current affairs programme.”

‘The most iconic Kubrick film’

Maybe making such a film about ‘le petit caporal’ was a tall order, but Kubrick sounded relaxed when he discussed it in interviews. The production, he told one journalist, would take “considerably less” time than 2001: A Space Odyssey did: “The exterior shooting – battles, location shots etc – should be completed within two or three months. After that, the studio work shouldn’t take more than another three months.” He was offhand about borrowing “a maximum of 40,000 infantry and 10,000 cavalry” from the Romanian army, and he remarked that recreating Napoleonic campaigns was “not really as difficult as it first appears”. Nor was he worried about the budget. Many of the Romanian extras’ uniforms would be made of a special kind of paper – far cheaper than cloth, but indistinguishable on camera. And there would be no need to construct elaborate studio sets. “Most of the palatial interiors can be shot in real locations in where the furniture and set dressing are already there, and one has only to move in with a small documentary-size crew.” The result would be unprecedented. Until then, Kubrick declared, there had “never been a great historical film” and there had “never been a good or accurate movie” about Napoleon. Even Abel Gance’s critically worshipped five-hour saga, released in 1927, was dismissed as “really terrible... a very crude picture”. In contrast, his own Napoleon would be “the best movie ever made”.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt was certainly possible. If nothing else, Groen believes that Napoleon could have been “the most iconic Kubrick film”, combining “the slow pace of Barry Lyndon, the attention to detail of 2001: A Space Odyssey, the massed battlefields of Spartacus”. And Harlan believes that it would have been the perfect vehicle for his brother-in-law’s preoccupations: “Self-destructive actions by intelligent people, the poison of jealousy and revenge, the ways that brilliance, success and power can go hand in hand with egocentricity, vanity and the abuse of such power... these were the themes that always interested him. Just think of Lolita, Paths of Glory and Dr Strangelove.”

Tragically, the studio that had financed 2001: A Space Odyssey wasn’t persuaded. “Stanley only had a pre-production agreement with MGM,” says Harlan, “an agreement to make a plan, schedule and budget. These elements were delivered, but MGM did not proceed to the next stage.” Kubrick’s timing was unlucky?. Metro-Goldwyn-Meyer had just changed hands, and its new owners were more intent on building casinos than on funding monumental historical dramas with 50,000 military extras. Meanwhile, the arrival of Dino De Laurentiis’s own Napoleonic epic, Waterloo (1970), offered “no encouragement”. To paraphrase Abba, Kubrick was finally facing his Waterloo in more ways than one.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt was a sad end to what Harlan describes as “two years of total dedication”, but it didn’t slow Kubrick down. Having flirted with an adaptation of Arthur Schnitzler’s 1926 novella, Traumnovelle, which became Eyes Wide Shut three decades later, he went on to make A Clockwork Orange. In the circumstances, it is almost incredible that it was released only three years after 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Next came Barry Lyndon (1975), which incorporated some of Kubrick’s Napoleon research, and many of his innovative ideas about period dramas: using an ultra-fast 50mm lens, for instance, so that scenes could be lit with no more than candles, oil lamps and sunshine. It may not have been Napoleon, but perhaps it was the “great historical film” that no one else had managed.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWas he ever tempted to return to his earlier ion project? “Not seriously,” says Harlan, “because he knew he could not do justice to his vision or his thoroughness unless he had much more screen-time and a bigger budget. Television was out of the question. But this, of course, has changed.”

Indeed, television has changed so radically in recent years, in of the expense and scope of its output, that Kubrick’s friend Steven Spielberg has talked about producing a mini-series based on the Napoleon script. In 2013, Baz Luhrmann was mentioned as a potential director, and Cary Fukunaga (currently shooting the latest Bond movie) has since been touted. Harlan is convinced that the time is right at last. “TV now is technically superb, and a series of many hours and chapters is the ideal format for Stanley Kubrick’s Napoleon,” he says. “It will happen!”

Images produced by Javier Hirschfeld

Stanley Kubrick: The Exhibition is at The Design Museum in London until 15 September.

Love film? BBC Culture Film Club on Facebook, a community for film fanatics all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.