Why 2001: A Space Odyssey remains a mystery

Alamy

AlamyKubrick may have set out to make a science-fiction film, but 2001: A Space Odyssey, which turns 50 this week, is closer to home than we think, writes Nicholas Barber.

It’s been 50 years since the release of 2001: A Space Odyssey, and we’re still trying to make sense of it. Stanley Kubrick’s science-fiction masterpiece is regularly voted as one of the greatest films ever made: BBC Culture’s own critics’ poll of the best US cinema ranked it at number four. But 2001 is one of the most puzzling films ever made, too. What, for instance, is a shiny rectangular monolith doing in prehistoric Africa? Why does an astronaut hurtle through a psychedelic lightshow to another universe, before turning into a cosmic foetus? And considering that the opening section is set millions of years in the past, and the two central sections are set 18 months apart, how much of it actually takes place in 2001?

Kubrick himself wouldn’t be too upset by all this head-scratching. “You’re free to speculate about the philosophical and allegorical meaning of the film,” he told an interviewer in 1968, “but I don’t want to spell out a verbal road map for 2001 that every viewer will feel obligated to pursue or else fear he’s missed the point.” Kubrick’s co-writer, Arthur C Clarke, answered some of the story’s questions in his tie-in novel, which was published just after the film’s release. But the director edited out anything which might have made it too easy to comprehend. He likened the film to a painting and a piece of music, something to experience “at an inner level of consciousness”. And yet 2001 isn’t completely baffling. One thing which is clear is how much it has in common with some of his previous anti-war and anti-authority films, 1964’s Dr Strangelove in particular.

Alamy

AlamySeen from a distance, the two films could hardly appear more different. One is a farcical black-and-white arms-race satire featuring Peter Sellers in multiple roles; the other is a richly coloured, contemplative, interstellar sprawl, described on the original poster as an “epic drama of adventure and exploration”. But look at the similarities: the Cold War secrecy between the US and Russia, the boardrooms packed with middle-aged men in suits, the supposedly infallible machine which is intent on slaughtering the people who built it. Look at the Dr Strangelove scene in which Major Kong (Slim Pickens) rewires his plane’s bomb-bay doors, and the almost identical 2001 scene in which an astronaut deactivates his spaceship’s computer.

Alamy

AlamyAnd look at the convictions which underpin both works: that humans are intrinsically, self-destructively violent, and that anyone who believes himself to be 100% right is probably a dangerous maniac. It may be going too far to call 2001 a cynical political comedy, but if Kubrick hadn’t wanted us to laugh, he wouldn’t have focused on a “zero-gravity toilet”. And he wouldn’t have had a chapter entitled The Dawn of Man, in which man, having dawned, bashes another man’s brains out with a club.

Great apes

In this opening sequence, our hairy ancestors (played by mime artists in costumes) eat nothing but roots and berries until they happen upon a towering black slab which was once compared to a tombstone but which now brings to mind an oversized iPhone. This mysterious monolith accelerates the ape-men’s learning, and one of them has the idea to use a bone as a weapon. After he has killed both a tapir and a fellow ape-man, he flings the bone high into the air, and Kubrick brings us the edit which always pops up when you type “match cut” into a search engine: the spinning bone is replaced by a satellite orbiting the Earth. Except that it’s not a satellite, as such. According to Clarke, the craft which takes the place of the bone is “supposed to be an orbiting space bomb, a weapon in space”. Here, at least, we can see what Kubrick is getting at: by his reckoning, human progress has all been about developing bigger and better ways to murder each other.

Alamy

AlamyIn this part of the film, we meet Heywood Floyd (William Sylvester), a scientist on his way to the Moon, where another alien monolith has been unearthed. But Floyd is no conventional sci-fi boffin: neither a crazed nerd in a lab coat nor a dashing intergalactic hero. Instead, he is a complacent, all-American breadwinner who is tended to by pretty stewardesses, and who misses his daughter’s birthday party because he is ‘travelling’. When he compliments his colleagues on their discovery, you wouldn’t think they had found proof of extra-terrestrial life; you’d think they had composed a new advertising jingle. “Well, I must say,” chuckles Floyd, “you guys have certainly come up with something.” Whether it’s the American generals in Dr Strangelove, the French generals in Paths of Glory, or the Minister of the Interior who claims to have the cure for crime in A Clockwork Orange, Kubrick enjoys pointing out that the men in charge of our fates aren’t necessarily the most imaginative or intelligent people in the solar system. And it’s always men. The only female character in Dr Strangelove is a US General’s bikini-wearing secretary; in 2001, the women have more clothes, but they don’t any have more dialogue.

‘Dr Strangelove in Space’

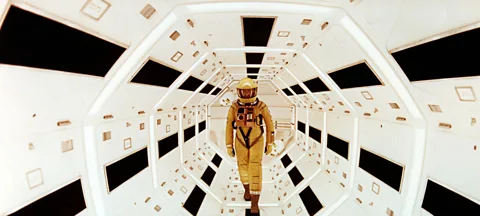

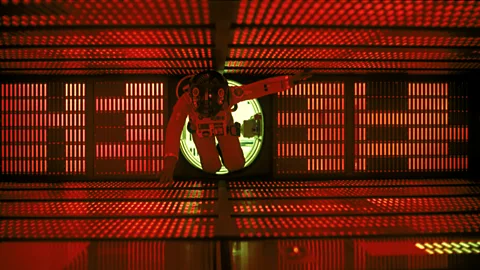

The film’s third section is set aboard a colossal spacecraft bound for Jupiter. Its crew consists of David Bowman (Keir Dullea) and Frank Poole (Gary Lockwood), along with three other astronauts in suspended animation, but most of the ship’s operations are taken care of by a computer named HAL 9000 (voiced by Douglas Rain). Could this artificially intelligent pilot spell trouble for his crewmates? Well, he declares that he is, “by any practical definition of the words, foolproof and incapable of error”, and that sort of self-confidence in a Kubrick film is usually a bad sign. Sure enough, HAL tells David and Frank, incorrectly, that the ship’s communications dish is faulty. Assuming that HAL must be malfunctioning, the astronauts decide that they’ll have to shut him down. Unfortunately, HAL decides to shut them down first.

Alamy

AlamyIt’s here, especially, that 2001 could be retitled ‘Dr Strangelove in Space’ because it’s here that Kubrick zeroes in on our puffed-up certainty, and of our absurd faith in any system or machine which seems to have all the answers. In the 1964 film, a ‘doomsday device’ that was supposed to guarantee world peace is actually going to wipe out civilisation – and it has been programmed to ensure that no one can stop it. And in the 1968 film, the ironies pile up even higher. A HAL computer makes a mistake. A mission controller confirms that is a mistake – because his own identical HAL computer on Earth says so. But HAL remains as sure of himself as the generals in Dr Strangelove: “Well, I don’t think there is any question about it,” he purrs, in his soothing, almost-emotional voice. “It can only be attributable to human error.” Listen closely and you can hear Kubrick groaning in despair.

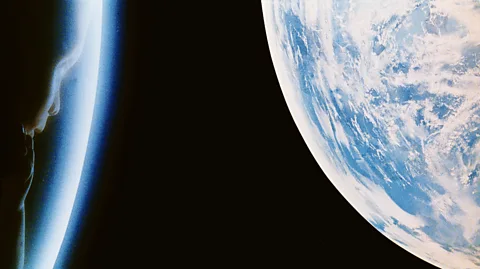

Alamy

AlamyNot that 2001 is simply a Dr Strangelove sequel. Ignore the bitter satire, and you’ve still got stunning special effects, immaculate production design, prophetic technology, transporting classical music, and all-out strangeness: Dave’s climactic voyage ‘beyond the infinite’ is as mind-blowing now as it must have been in 1968.

Nonetheless, it’s striking that Kubrick set out to make ‘the proverbial good science fiction movie’, to borrow Clarke’s phrase, and that he was fascinated specifically by alien life. And yet he couldn’t help commenting on human life instead. It’s one reason why 2001 is so satisfying, as cryptic as it may be. Kubrick was dreaming of other worlds, but he kept coming back down to Earth.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.