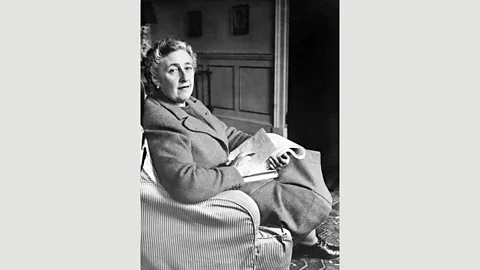

Agatha Christie shaped how the world sees Britain

Getty

GettyThe mystery writer is the world’s best-selling novelist and most translated author – so what are non-Brits learning about English people and culture through her stories?

For many, Agatha Christie is as quintessentially English as queueing for Pimm’s at Wimbledon. But as the best-selling novelist in history, her reputation goes far beyond the UK.

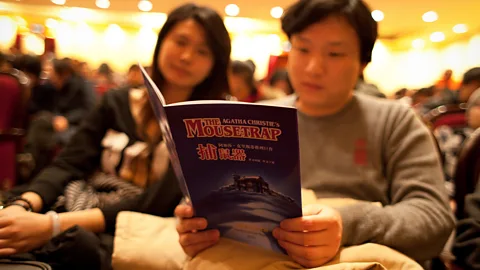

AFP/Getty

AFP/GettyHer works are seen as so easy to read, she’s a favourite author of people learning English. Christie is also, by leaps and bounds, the world’s most translated author – so if many people are learning the English language through Christie, they are learning about the English people through her, too. This is obvious, for instance, in the Collins English Readers series of abridged Christie books, whose cultural notes explain such topics as English village life and the saying ‘No smoke without fire’.

More like this:

The Los Angeles-based podcast hosts Catherine Brobeck and Kemper Donovan agree. Brobeck and Donovan broadcast the podcast All About Agatha, which has the ambitious aim of discussing and ranking all of Christie’s 60-plus novels.

For Brobeck, Christie was not only the first adult author she read heavily, but her first major exposure to English culture. “Of course that influences your idea of Englishness,” she says.

If Agatha Christie is continuing to influence readers’ ideas of Englishness, what exactly are they learning – and is any of it true?

Getty

GettyChristie’s version of Englishness is “there to be played with, rather than grimly realistic,” says the University of Hull English lecturer Sabine Vanacker. As with other classic crime fiction, her settings and characteristics take some artistic licence and even have elements of caricature. In reality, of course, not every British village has a kindly vicar, a blowhard colonel, a brittle lawyer, and a twinkling doctor – or indeed a preponderance of murderers. There’s also a surprising lack of pubs in her stories.

But not all of Christie’s version of Englishness is fanciful.

“The self-deprecation to me is what really comes through,” says Donovan. He sees something particularly English about the way Christie, either through her narration or her characters, uses dry wit, often gallows humour. In the short story Triangle at Rhodes, for example, she writes of one Englishwoman abroad:

“Unlike most English people, she was capable of speaking to strangers on sight instead of allowing four days to a week to elapse before making the first cautious advance as is the customary British habit.”

This kind of humour was very much part of the author’s personality, says Janet Morgan, (author of an official biography of Agatha Christie). Morgan explains that while Christie had strong beliefs about good and evil. “She was a very humorous person… She was amused by life, and by human beings, and by how they behaved.”

Getty

GettyWe see this in Peril at End House, when Captain Hastings, the detective’s sidekick who is a stalwart, stolid emblem of Englishness, expresses misgivings to Hercule Poirot, the preening Belgian detective who is Christie’s most famous character. In Hastings’ view, a possible motive that Poirot has advanced is too melodramatic.

Poirot replies: “It sounds, you would say, un-English. I agree. But even the English have emotions.”

Like the other foreign characters in Christie’s work, Poirot brings English stereotypes into relief. Christie relies on certain stock traits for her characters of different nationalities. The French are hotheaded, Scots are thrifty, and Australians are simple. Christie, who enjoyed travelling both before and during her marriage to her archaeologist husband, brings an incisive (but sometimes xenophobic) wit to her depictions of them all.

The English are not exempt. One age from Cards on the Table, which gently mocks English parochialism,says:

“Every healthy Englishman who saw him longed earnestly and fervently to kick him!... Whether Mr Shaitana was an Argentine, or a Portuguese, or a Greek, or some other nationality rightly despised by the insular Briton, nobody knew.”

Getty

GettyChristie experienced English anxiety about foreignness first-hand. The biographer Morgan relates that during a journey Christie took to Baghdad, “a rather bossy, self-important Englishwoman almost tried to adopt her.” Christie was able to shake off her would-be protector and escape into the desert. She also came away with a template for writing a certain kind of English character who thought that foreign things were frightening and needed to be guarded against.

Morgan says that another trait Christie pokes fun at in her English characters is the “conventionality which prevented people, for instance, from thinking that the parlourmaid might have seen something or might indeed be a murderer.”

For instance, in Peril at End House, Hastings takes a liking to a wholesome-seeming commander. Poirot sniffs:

“Doubtless he has been to what you consider the right school. Happily, being a foreigner, I am free from these prejudices, and can make investigations unhampered by them.”

Poirot – who its at the end of Three Act Tragedy that he exaggerates his foreign accent and his boasting so that the English don’t take him seriously – doesn’t have the respect for propriety that is integral to Christie’s depiction of Englishness, either. Crime, in Christie’s work, actually serves to uphold and draw attention to the social order.

Convention and decorum crop up not only in descriptions of Hastings, who believes ionately in them, but in another quintessentially English character of Christie’s: Jane Marple, the elderly woman residing in the village St Mary Mead. As Anna Marie-Taylor writes in Watching the Detectives, “the imprint of acceptability in St Mary Mead is Englishness, which is constituted as balance, common sense, reasonableness, sympathy, a notion of fair play and tradition and an ability to garden. Those qualities are articulated most fully by Miss Jane Marple.”

The podcaster Brobeck says that “Miss Marple is essentially invisible.” While Christie’s English characters often underestimate Poirot because of his flamboyant foreignness, they frequently dismiss Marple because of her gender and age. Like Poirot, Marple uses this as an opportunity. “That allows [Marple] into places in the class structure that otherwise might not be there,” Brobeck notes.

The class divide

In fact, class consciousness is Brobeck’s biggest impression of Englishness from Christie’s work. This send-up remains relevant even several decades after Christie’s death, though much of the current English anxiety over class is defused in a typically tongue-in-cheek way. From the men’s magazine Shortlist pitting celebrities against each other in its ‘Middle Class War’ feature, to just about every UK newspaper running quizzes for readers to test their poshness, an ironic obsession with class continues to feature in English society.

Christie’s characters are constantly revealing their anxieties as well as their minute understandings of class relations, with distinctions that can seem bewildering to the non-English. In A Murder Is Announced, for instance:

“Mrs Easterbrook greeted Phillipa Haymes with a little extra cordiality to show that she quite understood that Phillipa was not really an agricultural labourer.”

AFP/Getty Images

AFP/Getty ImagesWhile Christie’s characters are largely middle-class and often leisured, class consciousness is a feature of all social groups in her universe. In The Clocks, an excitable servant shows the police into a dining room rather than the drawing room in scrupulous recognition of their in-between status: as neither gentlemen nor commoners.

More generally, lecturer Vanacker says, Christie “questions Englishness a lot.”

In A Murder Is Announced, with its anxieties about the modernisation of a village and the influx of strangers, for example, we see tensions over what version of ‘Englishness’ is authentic. This continues to be a preoccupation in England.

But ultimately, Morgan says, “Some of the things that Agatha Christie identified are present in every society.” The settings and send-ups may seem specific. But the themes and character traits remain universal. And Christie’s insight into the foibles of not merely Englishness, but human nature, is just one clue to her enduring popularity far beyond this sceptred isle.

This story is a part of BBC Britain – a series focused on exploring this extraordinary island, one story at a time. Readers outside of the UK can see every BBC Britain story by heading to the Britain homepage; you also can see our latest stories by following us on Facebook and Twitter.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.