The Book of Kings: The book that defines Iranians

Alamy

AlamyAn epic poem written in the 11th Century helped save the Persian language, writes Joobin Bekhrad.

To say that, by and large, we Iranians are proud of our ancient culture and the Persian language – often to a fault – is to point out the obvious. In naming our children, we look back to our emperors and the legendary heroes of ancient Iran. We revel in the syrupy sweetness of Persian as the words of Hafez, Rumi and myriad other mystics and bards languidly roll off our tongues, leaving us and our audiences spellbound. We believe, as Sa’di once wrote, that mankind is one, but nonetheless regard our roots and distinct identity with an ineffable reverence and joy. Yet, there might have been relatively little left of our indigenous culture and the Persian language to celebrate today, had one particular poet not been around.

More like this:

Completed by Abolqasem Ferdowsi in the early 11th Century, the Shahnameh (Book of Kings) is not only a literary masterpiece, but also a book that has for centuries helped define Iran and the Iranian peoples, as well as safeguard the existence of the Persian language. Consisting of more than 50,000 rhyming couplets, it is the longest poem ever written by a single author. It is not an epic about a single defining event, a fantastical voyage, or a particular pair or star-crossed lovers or arch-rivals, as is the case with many national epics. Although certainly brimming with the aforementioned, the Shahnameh is an epic centred around the very essence and soul of Iran; and, while ancient Iran is its chief object, the book’s messages are timeless, and in many cases may well have been written for humanity as a whole.

Breaking the silence

To appreciate the importance of Ferdowsi’s magnum opus, it is crucial to understand the context in which it was written. After the Arab invasion of Iran in the 7th Century and the fall of the Sassanian Empire, there followed one of the darkest periods in Iran’s history. Under the reign of Iran’s foreign occupiers, adherents of its indigenous monotheistic Zoroastrian faith were persecuted, libraries were burned, and the Persian language vehemently suppressed during, as Iranians term it, the ‘two centuries of silence’. With Islam being the new order of the day, and Arabic the language of Iran’s new governors, the Persian language was, as with Zoroastrianism and indigenous Iranian culture as a whole, at risk of extinction. While some submitted to the yoke of the occupiers and tried to find a place for themselves within a strange new world, other Iranians chose to resist.

Alamy

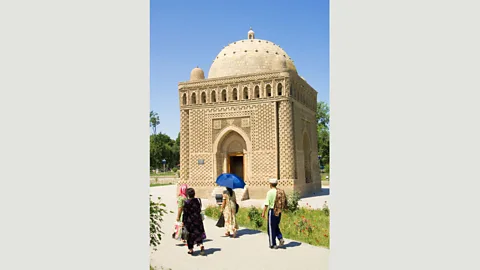

AlamyBefore his time, Ferdowsi’s home province of Khorasan in northeast Iran had been a hotbed of popular uprisings against Iran’s Arab occupiers, and the region in general was enjoying a revival of all things Persian under the reign of the Iranian Samanids between 819 and 1005 AD, istratively based in Bukhara in present-day Uzbekistan. Poets like Rudaki were amongst the first after the ‘two centuries of silence’ to write in Modern Persian, which had evolved from the Middle Persian of the Sassanian era; and, by the time Ferdowsi set to work on the Shahnameh, there already existed two other versions of it. The 10th Century poet Daqiqi had written some 1,000-odd verses of his Khodainameh, based on a book now known as the Abu Mansuri Shahnameh, after its patron, one Abu Mansur. Daqiqi, however, was killed by his slave before he could complete his paean to Iran; and so, picking up where Daqiqi had left off (his verses are included and acknowledged in Ferdowsi’s version), Ferdowsi sat down to finish the story with the of his Samanid patrons.

From Aryanam Vaejah to Iran

Simply put, the Shahnameh is a compendium of indigenous, pre-Islamic myths, legends, and historical episodes relating to the Irano-Aryans, written in a relatively ‘pure’ form of Modern Persian largely devoid of foreign loanwords. Although Iran’s national epic, the emphasis is on the Iranians as a people, especially as the Iran in the Shahnameh does not necessarily correspond to modern-day Iran, or even the Iran of Ferdowsi’s time. Aside from its ever-changing borders, one also needs to consider the difference between the ancient Iranian homeland – Aryanam Vaejah, meaning ‘Land of the Aryans’ – and present-day Iran (a simplification of Aryanam Vaejah, simply meaning ‘Aryan’), to which the Iranians migrated.

According to Dick Davis, translator of the Penguin edition of the Shahnameh, Aryanam Vaejah “was almost certainly [in] Central Asia: modern Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, [and] Tajikistan”. It is for this reason, for instance, that the Alborz Mountains Ferdowsi speaks of, and which are so central to Zoroastrian lore, are not the present-day ones in northern Iran, or why, as Davis says, “the modern Sistan is largely to the west of the ancient Sistan”. Expanding on the location of Iran in the Shahnameh, Davis posits that: “In the poem’s mythical and early legendary sections, Iran is in what is now northern Khorasan, and reaches as far north as present-day Bokhara and Samarkand … and it reaches as far east as the Helmand province in Afghanistan … With the Sassanians, Iran becomes more or less modern Iran.”

Alamy

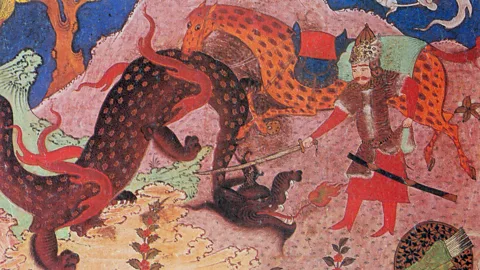

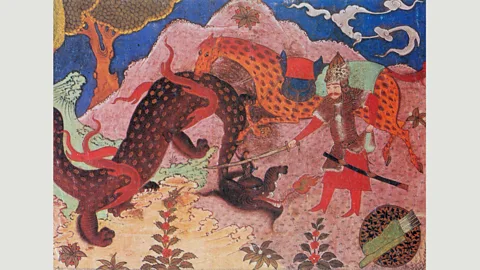

AlamyOne of the things that makes the Shahnameh such a singular epic is its sheer breadth. Scholars typically divide the book into three ‘ages’. The first, the mythical, begins with the world’s creation and the reign of Keyumars, the first Iranian king (and man on Earth), and continues with stories such as that of the legendary Jamshid and his fall from grace, and the foreign, demonic Zahhak, who is buried alive by the blacksmith Kaveh.

From here, the story progresses to the heroic age, which contains the bulk of the epic’s most beloved and well-known tales, and which has at its core the rivalry between the Iranians, west of the Oxus River in Central Asia, and the Turanians to the east. Although Ferdowsi calls the Turanians ‘Turks’ in his poem (as Turks inhabited the area in his lifetime), they are actually Iranian. “[The Turanians] are clearly a separate branch of the Iranian people,” says Davis. “The Iran-Turan rivalry … almost certainly derives from a dimly ed prehistoric enmity between two branches of the Iranian peoples.”

Alamy

AlamyIf there’s one character any Iranian can name from the Shahnameh, it’s Rostam. A valiant hero like none other in the book, he battles with divs (devils), gets kings out of sticky situations, and, like Hercules, undergoes seven trials. He also happens, in a case of mistaken identity, to kill his son, Sohrab, in one of the epic’s most tragic and harrowing episodes. Also of note is the ill-fated Siyavash, who, after proving his innocence in a trial by fire (having been accused of rape by his lusty, scheming stepmother), is later murdered at the hands of the Turanians. Ending with the death of Rostam, the book makes a jump of sorts to the historical age, which begins with the invasion of Alexander, and ends – on a rather caustic note – with that of the Muslim Arabs in the 7th Century. Although they use historical events and figures as starting points, the stories here have been greatly embellished and exaggerated for dramatic effect.

While things started out well for Ferdowsi, he didn’t have a particularly happy ending. Before he could complete the book, his Samanid patrons were vanquished by the Ghaznavid Turks. According to the 12th-Century Persian writer Nezami Aruzi Samarkandi, instead of the 60,000 dinars Ferdowsi had been promised, the Ghaznavid ruler Sultan Mahmud only dished out 20,000 dirhams in the end, not appreciating the significance of the book before him. Depressed, Ferdowsi then, according to Samarkandi, went to a bathhouse, had a beer, and gave the money to the attendants there.

Later, feeling remorse for his behaviour towards the poet upon whom, as the introduction of one extant Shahnameh manuscript suggests, he had conferred the sobriquet ‘Ferdowsi’ (‘Paradisiacal’), Sultan Mahmud sent 60,000 dinars’ worth of indigo to Ferdowsi. But alas, it was too late: at the same time the indigo was being delivered, Ferdowsi’s corpse was being taken to the cemetery, where it was denied burial on of his professed Shi’a faith. He died a poor and brokenhearted man and was buried in his own orchard.

A legend after his lifetime

Although downcast at the time Sultan Mahmud snubbed him, Ferdowsi knew what he’d achieved. Amongst Iranians today, Ferdowsi enjoys a status comparable with that of Cyrus the Great. So much is he revered and honoured that some have even credited him with singlehandedly saving the Persian language from oblivion, not to mention the memory of many of Iran’s ancient myths and legends. This, according to Davis, is ‘unwarranted’, as the Persian revival had been in full swing before Ferdowsi’s time. “Nevertheless,” he says, “it’s certainly the case that the Shahnameh put Persian on the map in a way that no previous poem had done”.

Alamy

AlamyIn spite of the fact that the heroes of the Shahnameh are overwhelmingly Aryan Zoroastrians, and that the stories take place in ancient, often remote times, the book has managed to transcend ethnicity, religion, geography, and time. “One of the definitions of a major literary work,” says Davis, “is that it speaks cogently to different generations, and not necessarily in the same way for each generation, and the Shahnameh has done this for many people for a thousand years”. Yes, the tales are riveting and masterfully composed; but they are also didactic, replete with life lessons, sage advice, and observations on the ways of the world. Ferdowsi extols wisdom, faith, courage, patriotism, and justice, warns his readers of the fickleness of fortune, and – notwithstanding the self-determining Zoroastrian faith of his heroes – laments the ineluctability of fate. As such, the Shahnameh is as edifying as it is entertaining.

A favourite of every Iranian dynasty, whether native or foreign, since its completion, and adored by the Ottoman Turks and the Mughals of India, it is still revered in a multitude of countries, from Turkey and Georgia in the West, to Tajikistan in the East, to name only a few. It has also featured prominently in contemporary works of literature and art, such as Orhan Pamuk’s My Name is Red, Khaled Hosseini’s The Kite Runner, and Shirin Neshat’s Book of Kings series of portraits. And, while the Shahnameh – with its celebration of royalty and pre-Islamic Iran – has been considered anathema by some in Iran since the 1979 Revolution, Ferdowsi’s detractors there have had no choice but to embrace him, so firmly rooted is he in the hearts of Iranians – and deservedly so. “Long did I toil during these decades three,” he famously wrote of his labours. “The Iranians I revived with this Parsi (Persian)”.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.