Scars from the world's first deep sea mining test 50 years on

USGS

USGSPresident Donald Trump is trying to fast track new deep sea mining efforts, but half a century after the world's first deep sea mining tests picked mineral-rich nodules from the seafloor off the US east coast, the damage has barely begun to heal.

Plunging to the ocean's abyss on the Blake Plateau, a deep-sea mountain range off the coast of North Carolina, is an otherworldly experience. It's like no other ocean bed that microbiologist Samantha Joye has ever visited. In her deep-sea submersible called Alvin – a three-person vessel made of titanium thick enough to withstand pressure in the ocean's depths, with two robotic arms reaching outside for sample collection – it takes more than an hour to descend to about 2,000m (6,600ft) below the water's surface.

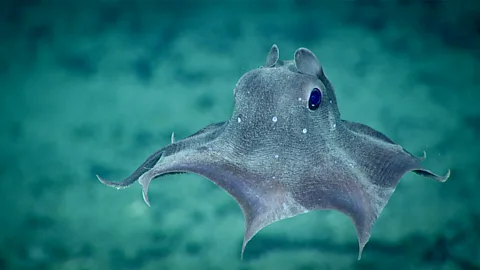

On the way down, the water is on fire with bioluminescence and abounds with wildlife. There are huge fish, small fish and jellyfish. Shrimp, sea slugs, octopuses and hundreds of squid bump into the submarine, seeming to be curious about its free fall into their home.

"I have worked all over the place, and my mind was blown on the Blake Plateau. I mean, it's just spectacularly diverse," says Joye, recalling her last trip to the plateau in August 2018. At touchdown, the silty floor is covered in worms, sponges, stars and mussels the size of an adult human's forearm, says Joye, gesturing to her own limb to show me.

Among the abundance of life, though, a section of the Blake Plateau is barren with the scars from the world's first deep-sea mining pilot test carried out in 1970. That experiment 50 years ago was just a proof-of-concept, but full-scale commercial deep-sea mining is on many of today's national to-do lists. In April 2025, US President Donald Trump signed an executive order to fast-track deep-sea mining.

The traces of those first rudimentary tests on the Blake Plateau are still visible today, half a century on, and scientists think they're just a small example of the effects deep-sea mining could have on the ocean ecosystem if it were to be conducted at scale.

Noaa Office of Ocean Exploration and Research

Noaa Office of Ocean Exploration and ResearchThe world's first deep-sea mining test was conducted by US company Deepsea Ventures in July 1970. A vacuum-cleaner-like machine bulldozed through the abyss and sucked up 60,000 baseball-sized lumps off the bottom of the ocean. The nodules – filled with manganese, nickel and cobalt that accumulate a few millimetres per million years – were hoped to become a resource for the nation's industrial endeavours. There remains high interest in them today, as they're replete with minerals for making batteries for electric cars and smartphones, as well as medical and military technology.

Deepsea Ventures' project fell through, and no more deep-sea mining was done off the US East Coast. But a remote-controlled robot sent to that segment of the Blake Plateau during a 2022 scientific expedition found the company's footprints. Scientists snapped pictures of defined dredge lines in the mud for more than 43km (27 miles). The lines dug into the abyss like train tracks, as if somebody had raked through it just recently, and the damage was "widespread and definable", according to reports. Where the tracks are, there is nothing: no nodules and no biodiversity. No curious squid. Nothing like the kaleidoscope of beauty Joye encountered in 2018, just around the corner.

While no data is available on what that part of the Blake Plateau looked like before the deep-sea mining experiments in the 1970s, the contrast between the desolate scraped mud tracks and the rest of the Blake Plateau is stark. (You can see these tracks in the image at the top of this article.) The site is a proxy for what might happen elsewhere, says Joye.

Before and after data from a mining simulation in an analogous area in the Pacific Ocean, the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, south-east of Hawaii and poised to be a deep-sea mining hotspot, suggests these ecosystems take hundreds of years to bounce back. Segments there that had been test-ploughed through in 1989 had much lower diversity of large animals, especially filter feeders, and still had up to just half of their microbial communities after 26 years.

Noaa Office of Ocean Exploration and Research

Noaa Office of Ocean Exploration and Research"And if you were thinking about something that was going to recover pretty quickly, it would be microbes, right":[]}