Indigenous mothers are being 'failed' in Australia – so they are taking measures into their own hands

Emmanuel Lafont/BBC

Emmanuel Lafont/BBCAboriginal mothers and their babies have higher death rates and poorer health outcomes than non-Indigenous Australians. New community-led services are trying to change that.

Edie recently gave birth to her fourth child. After the birth she took her placenta with her from hospital and buried it close to where she was born. It is something Edie – whose name has been changed to protect her identity for personal safety reasons – has done with each of her three children. The placenta, she says, is a baby's first home, so it is buried in what Indigenous Australians refer to as "on Country" to identify that place as the baby's home. It gives the newborns their first connection to the generations of ancestors that came before then and the land they inhabit.

The 35-year-old from Brisbane, Queensland, is one of a growing number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women who are turning to a movement known as "Birthing on Country" as an alternative to standard maternal services offered by the Australian healthcare system. It is a concept that aims to better meet the needs of Indigenous Australian mothers and their babies.

"Birthing on Country connects what we know as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the modern world to what our ancestors did," says Yvette Roe, a professor of Indigenous health at Charles Darwin University, Australia. "It's a concept with key elements: when we talk about 'Country', we're talking about ancestral connection to the country where we're born. We're talking about 60,000 years of connection to the land and sky."

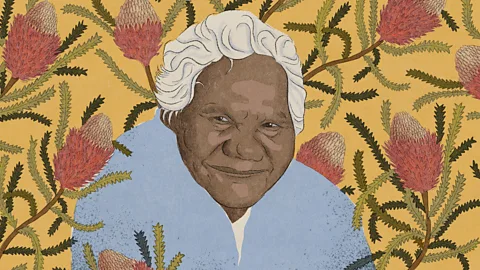

Roe, a proud Njikena Jawuru woman herself, is one of the co-directors of the Molly Wardaguga Research Centre at Charles Darwin University's Queensland campus, alongside Sue Kildea, a professor of midwifery. They are at the forefront of research, implementation and collaboration with Indigenous and non-Indigenous health and maternal services. The organisation, which was established in 2019, is named in tribute to the late Molly Wardaguga, a Burarra Elder of the Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory of Australia, an Aboriginal midwife and a pioneer of the Birthing on Country movement. It was born out of a growing recognition that standard maternal care in Australia was failing to meet the needs of Indigenous women.

In Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers are up to three times more likely to die during childbirth, and their babies are nearly twice as likely to die in their first year of life. Conditions relating to premature birth or complications during pregnancy are the major cause of infant morbidity and mortality in First Nations communities in Australia.

In 2021, preterm birth rates were 14.1% for babies born to First Nations women compared with 7.9% among non-Indigenous Australians, statistics that have changed little in over a decade.

It reflects broader gaps in the health and welfare of Aboriginal and Torrest Strait Islander people. High levels of discrimination, unemployment, poor quality housing and poor education among Indigenous Australians are among the factors that have led to worse health outcomes. It can also be difficult to access healthcare in the first place as many First Nations communities face travelling long distances to see a doctor, dentist or midwife.

Many Indigenous women live in remote areas, meaning they have to travel far from their homes to the nearest city hospitals to give birth, which can not only be expensive but also leave them feeling isolated and distressed, according to research from the Universtiy of Melbourne.

"The principle of Birthing on Country is that it is baby and woman-centred, rather than seeing birthing through a biomedical model where it is often just a transaction between a mother and a clinician," says Roe.

Emmanuel Lafont/BBC

Emmanuel Lafont/BBCSome women also feel deeply distrustful of the modern healthcare establishment due to the chequered history of medical experiments on Indigenous Australians and children being forcibly removed from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families. Indeed, First Nations children in Australia are still being removed at disproportionately high rates compared to the rest of the population.

Every four years, the Close The Gap report, published by the Australian Human Rights Commission, addresses key reforms needed to address the disparity in health outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people relative to non-Indigenous Australians. One of the key recommendations made in the report is the recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and their voices in research, policy and delivery of health services.

Birthing On Country is one attempt to do this by offering maternal care in a way that aims to recognise a woman's language and family, her health and social needs, according to its proponents.

While expecting her first child – her son – four years ago, Edie had heard bleak stories about the experiences her friends and family had had in hospital-based maternity services.

"They told me there was no sense of holistic care, and for some people that I'm close with, they felt concern around their cultural safety and the safety of their child in that hospital space," she says. "I have heard lots of firsthand experiences from many who have a distrust of the health services and the hospital system – especially with the overrepresentation of Aboriginal people having their children removed throughout history."

In response, Edie turned to her local Aboriginal health service to ask about her options.

"I wasn't sure exactly what I wanted, but I knew I wanted something culturally appropriate," she says. She eventually found the Birthing in Our Community (BiOC) programme, a multi-agency service operating in Queensland and New South Wales.

Since launching in 2003, over 1,000 women have used BiOC services, which are run by Mater Mothers' Hospital in South Brisbane and two First Nations community-controlled health services: the Institute for Urban Indigenous Health and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community Health Service Brisbane. Together they offer a system of maternal care that depends on a skilled First Nations workforce, multi-agency partnerships (community organisations, health practitioners, social workers), and a community hub or centre where these services are delivered.

All three of Edie's children have now been born within the BiOC programme. "It's been the most positive, beautiful experience, free of birth trauma," she says. "That entirely factored into my love and want for more children, which I attribute to BiOC."

Edie's care was provided by a team that included an obstetrician, an Indigenous family worker and one of four midwives. She says that her team of carers was primarily women, which gave her an additional level of assurance. "This is what women have been doing for millions of years together with other women," she says. "Birthing was a ritual, and it was always conveyed to me that it was beautiful."

A vital aspect of BiOC is its holistic, sensitive approach, says Kristie Watego, services development officer with the Institute of Urban Indigenous Health in Brisbane. Some of the women she deals with have difficulties that go beyond just their health, such as experiencing domestic violence, and so those too need to be considered.

"We provide great clinical care but first and foremost, we provide connection and being together, teaching mothers to advocate for themselves in a medical system which constantly overlooks them," she says. "Telling a woman in a domestic violence situation to eat better during her appointment is useless. We need to ask, 'what's going on for you and how can we you">window._taboola = window._taboola || []; _taboola.push({ mode: 'alternating-thumbnails-a', container: 'taboola-below-article', placement: 'Below Article', target_type: 'mix' });