Why it's proving difficult to define the official dawn of the Anthropocene

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt may be a widely-used term, but geologists still can't agree when the Anthropocene actually started.

When exactly did human beings begin influencing nature on a planetary scale? The answer is not clear-cut. Was it when people started farming in early history? The moment our pollution first bled into ecosystems? The Industrial Revolution? Or as recently as the 20th Century?

It's also a question that goes to the heart of a recent scientific disagreement about the Anthropocene.

On 5 March, media reports suggested that geologists had voted to reject a proposal that would recognise the Anthropocene officially. If you only read these headlines, it would be easy to assume that the entire concept has been binned. It's more subtle than that.

What these geologists are debating is when the Anthopocene began, and whether they need to update the stratigraphic record – the official timeline of Earth history that runs from the pre-Cambrian to the Holocene. They also lack consensus about whether humanity's impact so far should be defined as an "epoch", which typically lasts millions of years, or an "event", which is far shorter, within this record.

So, what does this mean for our understanding of the Anthropocene – are we actually in it, or not?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe term "Anthropocene" – popularised in the 2000s – has become a widely-used concept to describe our current moment in time: when human beings are having profound impacts on the living and physical world. We have transformed Earth's chemistry and atmospheric composition, triggered extinctions and speciations, and even created new rock types, such as "plastiglomerate" – a conglomeration of rock fragments, plastic debris and organic material.

But for geologists, the Anthropocene would have a more specific definition: a new epoch, with a new colour on the stratigraphic record, straight after the end of the Holocene. Crucially, this would mean choosing an agreed-upon "beginning" – both in time and space – and despite two decades of investigation, they've yet to decide.

Geological stages begin with a marker that can be traced to a single time, place and measurement. Sometimes it's the presence of a fossil not seen earlier in Earth's history. For example, the Jurassic officially begins in the Alps, where an ammonite called Psiloceras appears in rocks. Other times, these markers are defined using chemical or compositional changes in ice cores or minerals, for instance. Each one is called a "golden spike" (or more officially a "Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point".) When one appears in a rock formation, a gold piece of metal is sometimes hammered into place, like this one in Australia.

Over the past decade or so, a collection of geologists called the Anthropocene Working Group (AWG) has been examining how and where to define the Anthropocene's golden spike.

You may also like:

After years of scrutiny, in 2016 they chose a suite of markers that appeared around the mid-20th Century: these clear geological signatures are embedded in lakes, stalactites, coral reefs and ice cores around the world. They include evidence of nuclear weapons tests such as plutonium fallout, isotopes such as caesium-137 and strontium-90 used in the weapons, and a rapid increase in atmospheric carbon-14 caused by the explosions. There's also man-made deposits like microplastics and spheroidal carbonaceous particles (Ss), a type of ash produced by burning coal at high temperatures.

If future geologists studying a rock formation wanted to find when the Anthropocene began, they could look for these markers. In fact, some of the nuclear signatures like carbon-14 are even inside the human body, so archaeologists could one day find them embedded in the teeth, tissue or bones of people born since the 1950s.

Read more in this 2023 article: The atomic bomb marker inside your body.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhy the 20th Century though? As well as offering a clear geological signature that will be observable for tens of thousands of years, it was around this point that humanity's impacts began to accelerate, explains geologist Colin Waters of the University of Leicester, who is chair of the AWG. In their investigations, the group acknowledged that people had been altering nature for millennia, but from the 1950s onwards many of the metrics of planetary change suddenly shot up, from CO2 to ocean acidification.

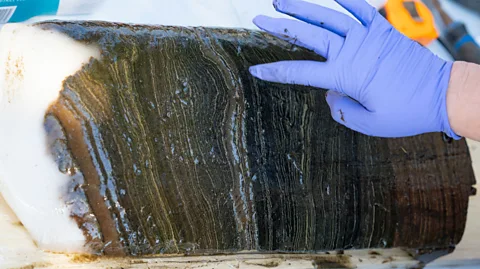

In mid-2023, the AWG also proposed a potential golden spike location. From various places around the world, including caves, coral reefs, and city ruins, they chose a lake in Canada. The deep, muddy sediments of Crawford Lake, west of Toronto, contain a range of the 1950s nuclear and fossil fuel markers that would allow future geologists to date the Anthropocene, says Waters. Geologists removed cores from the lake bed to store at a safe location.

However, the AWG was not in a position to make all this official – they could only make a recommendation to their parent organisations, the Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy (SQS) and the International Commission on Stratigraphy. And even within the AWG, there has been discord, prompting at least one resignation.

And it's in this scientific bureaucracy that the proposal appears to have hit the buffers. The AWG may want the change, but a number of colleagues have reportedly voted against them – at least according to results seen by the New York Times. Waters confirmed to the BBC that there had been a vote. It may not be final, but if it is recognised, then the plan that has been years in the making "cannot progress", he says.

The pushback appears to be over the AWG's choice of the mid-20th Century as a beginning: other researchers have argued, for instance, that a methane rise from the first farming could equally serve as a marker, or the uptick in lead pollution from early mining and smelting. Not to mention the massive increase in fossil fuel burning during the Industrial Revolution.

Differences of opinion are also present over whether the Anthropocene should be an "epoch", like the Holocene or the Palaeocene, or an "event", like a mass extinction. Geological events can be highly consequential on Earth, but they don't last millions of years.

So the question is not just when the Anthropocene began, but also when it will end. If humanity gets its act together within the next few hundred years, then the alarming perturbations of the 20th and early 21st centuries might not seem so epochal after all.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDoes this latest vote mark the end of the Anthropocene as a concept? Almost certainly not.

For starters, the results are not official unless authorised by senior of the SQS, including its chair, says Waters. "We note at this stage that there remain several issues that need to be resolved about the validity of the vote and the circumstances surrounding it."

In a statement on 6 Mar, the SQS suggested that the vote may not be final. "The alleged voting has been performed in contravention of the statutes of the International Commission on Stratigraphy," it said. The SQS chair, Jan Zalasiewicz of the University of Leicester, has requested "an inquiry including instituting a procedure to annul the putative vote".

The AWG "stands fully behind its proposal", says Waters. "We will continue to argue the case that the evidence for the Anthropocene as an epoch should be formalised."

And in any case, the term Anthropocene is not going away in popular culture. To the layperson, it might seem curious that a small group of scientists is apparently debating whether the Anthropocene is real or not – especially when they see the impacts of climate change, pollution, and more all around them.

The truth is, no-one is saying that humanity is not having a profound impact on Earth. When it actually began may be more important to geologists than the person on the street, but how long it will last? That's something that affects everyone, no matter how you define it.

*Richard Fisher is a senior journalist for BBC Future, and the author of The Long View: Why We Need to Transform How the World Sees Time.

--

If you liked this story, Why hurricane season this year will not be normal.