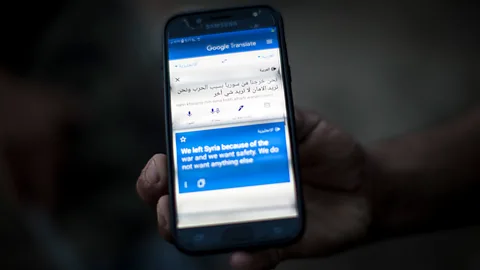

That language barrier can pose a problem for anyone who needs to gather precise, global information in a hurry – including intelligence agencies.

Mohammed Elshamy/Getty Images

Mohammed Elshamy/Getty Images"I would say the more interested an individual is in understanding the world, the more one must be able to access data that are not in English," says Carl Rubino, a programme manager at IARPA, the research arm of US intelligence services. "Many challenges we face today, such as economic and political instability, the Covid-19 pandemic, and climate change, transcend our planet – and, thus, are multilingual in nature."

Training a human translator or intelligence analyst in a new language can take years. Even then, it may not be enough for the task at hand. "In Nigeria, for instance, there are over 500 languages spoken," Rubino says. "Even our most world-renowned experts in that country may understand just a small fraction of those, if any."

To break that barrier, IARPA is funding research to develop a system that can find, translate and summarise information from any low-resource language, whether it is in text or speech.

Picture a search engine where the types in the query in English, and receives a list of summarised documents in English, translated from the foreign language. When they click on one, the full translated document comes up. While the funding comes from IARPA, the research is carried out openly by competing teams, and much of it has been published.

Kathleen McKeown, a computer scientist at Columbia University who leads one of the competing teams, sees benefits beyond the intelligence community. "The ultimate goal is to facilitate more interaction between, and more information about, people from different cultures," she says.

The research teams are using neural network technology to tackle the problem, a form of artificial intelligence that mimics some aspects of human thinking. Neural network models have revolutionised language processing in recent years. Instead of just memorising words and sentences, they can learn their meaning. They can work out from the context that words like "dog", "poodle", and the French "chien" all express similar concepts, even if they look very different on the surface.

To do this, however, the models usually need to go through millions of pages of training text. The challenge is to get them to learn from smaller amounts of data – just like humans do. After all, humans don't need to read years' worth of parliamentary records to learn a language.

You might also like:

"Whenever you study a language, you would never, ever in your lifetime see the amount of data today's machine translation systems use for learning English-to-French translation," says Regina Barzilay, a computer scientist at MIT who is a member of another of the competing teams. "You see a tiny, tiny fraction, which enables you to generalise and to understand French. So in the same way, you want to look at the next generation of machine-translation systems that can do a great job even without having this kind of data-hungry behaviour."

To tackle the problem, each team is divided into smaller specialist groups that solve one aspect of the system. The main components are automatic search, speech recognition, translation and text summarisation technologies, all adapted to low-resource languages. Since the four-year project began in 2017, the teams have worked on eight different languages, including Swahili, Tagalog, Somali and Kazakh.

Maciej Luczniewski/Getty Images

Maciej Luczniewski/Getty ImagesOne breakthrough has been to harvest text and speech from the web, in the form of news articles, blogs and videos. Thanks to s all over the world posting content in their mother tongues, there is a growing mass of online data for many low-resource languages.

"If you search the internet, and you want data in Somali, you get hundreds of millions of words, no problem," says Scott Miller, a computer scientist at the University of Southern California who co-leads one of the research teams working on this. "You can get text in almost any language in fairly large quantities on the web."

This online data tends to be monolingual, meaning that the Somali articles or videos are just in that language, and don't come with a parallel English translation. But Miller says neural network models can be pre-trained on such monolingual data in many different languages.

It is thought that during their pre-training, the neural models learn certain structures and features of human language in general, which they can then apply to a translation task. What these are is a bit of a mystery. "No one really knows what structures these models really learn," says Miller. "They have millions of parameters."

But once pre-trained on many languages, the neural models can learn to translate between individual languages using very little bilingual training material, known as parallel data. A few hundred thousand words of parallel data are enough – about the length of a few novels.

The multilingual search engine will be able to comb through human speech as well as text, which presents another set of complex problems. For example, speech recognition and transcription technology typically struggles with sounds, names and places it has not come across before.

"My example would be a country that's maybe relatively obscure to the West, and perhaps a politician gets assassinated," says Peter Bell, a specialist in speech technology at the University of Edinburgh who is part of one of the teams trying to tackle this problem. "His name is now really important, but previously, it was obscure, it didn't feature. So how do you go and find that politician's name in your audio">window._taboola = window._taboola || []; _taboola.push({ mode: 'alternating-thumbnails-a', container: 'taboola-below-article', placement: 'Below Article', target_type: 'mix' });