Why the 'post-natural' age could be strange and beautiful

Vincent Fournier

Vincent FournierHumanity has changed nature profoundly, but it may be only the beginning. Researcher Lauren Holt explores what the far future could bring for the planet’s organisms – and for us.

At 4913 Penn Ave, Pittsburgh, there is an unusual institution. The Center for PostNatural History is a small museum with an eclectic and bizarre mix of specimens: you will find a rib-less mouse embryo, sterile male screwworm, a sample of E. coli x1776 (a specimen designed to be harmless and unable to survive outside the laboratory), and a stuffed transgenic BioSteel goat named Freckles, genetically modified to produce spider silk proteins in her milk.

The museum’s subject, post-naturalism, is the study of the origins, habitats, and evolution of organisms that have been intentionally and heritably altered with genetic engineering, and the influence of human culture and biotechnology on evolution. Its tagline: “That was then. This is now”, complements its logo, an evolutionary tree with an arrow ing two distinct branches. Visitors are encouraged to consider that each specimen has a natural, evolutionary history, as well as a post-natural, cultural one.

You might also like:

As long as humans have existed, we have been influencing our planet’s flora and fauna. So, if humanity continues to flourish far into the future, how will nature change? And how might this genetic manipulation affect our own biology and evolutionary trajectory? The short answer: it will be strange, potentially beautiful and like nothing we’re used to.

Center for PostNatural History

Center for PostNatural HistoryRomantically perhaps, we still view anything that hasn’t been selectively bred, industrialised, or deliberately genetically altered as natural and “pristine”. However, there remains very little of nature that does not bear the sticky fingerprints of humanity in some way. Since our ancestors spread out of Africa some 50-70,000 years ago, snacking on all the megafauna on the way and thereby radically changing the landscape, our species has been shaping and transforming nature.

Around 10,000 years ago, we began selectively breeding organisms we found the most desirable, thereby altering the genetic composition of species. Today, technology has only accelerated this practice. The sperm from a prize bull can be collected and thousands of cows impregnated from that one male, a feat impossible for even the most determined bovine Casanova. From cattle to pet dogs, we have propagated these bred organisms all over the world, creating a huge biomass that wouldn’t exist without us, and introduced cosmopolitan breeds that test the limits of physiology for aesthetic or agricultural benefit.

Maria McKinney

Maria McKinneyOver millennia, our influence on many taxonomic groups has been profound. Our food demands mean that 70% of all birds currently alive are chicken and other poultry, enough to create their own geological strata. Meanwhile, human hunting, competition and habitat destruction has killed off so many large fauna that the average size of mammals has shrunk, according to the paleo-biologist Felisa Smith at the University of New Mexico. There have already been irreversible losses of biodiversity and species.

Yet our impact on nature so far may only be the beginning. New genetic tools promise a step change in our ability to manipulate organisms. We are moving into future where selecting positive traits in crops or animals arising from natural variation, still a laborious and time-consuming process, is no longer necessary. With ever more precise genomic editing techniques, such as Crispr-Cas9, we can move suites of genes between species, drive certain genes preferentially through natural populations – and even create wholly synthetic organisms. As such, bioengineering represents a new form of genetic information transfer, creation, and inheritance.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe modification of organisms also extends to irreversibly exterminating certain species. Although humans have been waging war on Anopheles mosquitoes for hundreds of years, via chemical, mechanical and other means, they remain one of humanity’s greatest natural enemies. Biotechnology has allowed the creation and release of hordes of sterile males, designed to crash population numbers when they mate with wild females, and now, mosquitoes that contain “gene-drives”, which accelerate ing a sterility mutation into the next generation, have also been developed.

With climate change really taking hold, scientists and policy makers have started to prioritise “ecosystem services” essential to humans, such as pollination and the replenishment of fish stocks, and are considering how bio-engineered organisms or mechanical agents could be released into the wild.

For example, since coral in the Great Barrier Reef is in terminal decline, research is ongoing into how to release heat-resistant zooxanthellae, the photosynthesising symbiote of coral polyps, into the ocean. Walmart has patented mechanical pollinator drones, seemingly looking to future-proof its operations. And the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (Darpa) has also recently awarded grants to develop genetically engineered insects that carry viruses for the gene-editing of plants, ostensibly for altering crops in the field, but such technologies could conceivably be extended to ecosystems.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIf we extend our lens to the far future, how will these technologies change our relationship with the rest of life on Earth? Various trajectories lay in front of us, from the holistic to the truly strange.

Firstly, it is possible that we may decide to scale back our manipulation of nature and the wild. After all, there are very prescient concerns as to what could go wrong: for example, off-site genetic damage whereby the molecular “scissors” used to cut and insert pieces of DNA produce unintended effects, or recipient ecosystems become unstable in other, unpredicted ways.

In this potential future trajectory, humans might collectively decide to re-wild nature, and make space for the non-human to exist on a well-functioning planet, recognising that the biosphere (although already heavily influenced by humans), still represents a relatively whole and billion-year stress-tested form of adaptive complexity.

This would probably be the most effective way to protect ecosystems and ensure human survival on planet Earth for the long-term. We could re-wild a significant proportion of the planet, and concentrate food production into multi-story inner city locations. It would be an action I would argue, that respects all the forms – deer, wolves, bluebells, giraffes, even humans – that life takes presently, in the knowledge that things will slowly evolve and eventually change without explicit interference.

Yet, much as I might wish it, I’m not sure that future trajectory is very likely. There will probably be a national and market arms-race to develop and implement technologies that will continue to tamper with nature, not least to protect or patent essential ecosystem services in the Anthropocene, or in the name of defence, but also since humanity’s powers and curiosity to manipulate the raw materials of life are seductive and ever-increasing. At the same time we are becoming ever more separated from other organisms and ecosystems. In such a severed state it is easier to conceive of radically altering the fabric of nature to wholly human interests.

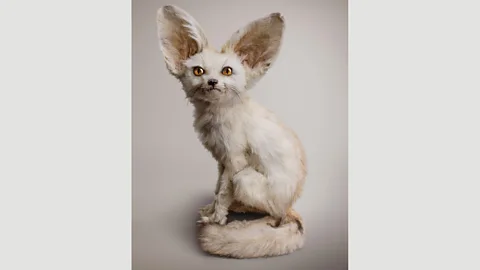

Artists have speculated about what this might look like, such as Vincent Fournier, who has imagined some of the chimeric organisms we might create: some designed to promote rainfall, others to respond to pollution.

Vincent Fournier

Vincent Fournier Vincent Fournier

Vincent FournierIn the film Blade Runner, the screenwriters portrayed a world with manufactured humanoids and animals, owned by the corporations that created them. This dystopian future may have some truth to it, given that even in the present day engineered organisms – such as the BioSteel goat on display in the Center for PostNatural History – are owned via the intellectual property rights of their augmentations. It is conceivable that whole ecosystem services – pollination, for instance – will be owned by certain corporations.

These bioengineered agents are likely to be more “fit” than their predecessors and become competitors, since they will be deliberately engineered for either satisfying human aspirations (and therefore will be preferentially under our protection), or for survival in an anthropically altered world. As such, modified organisms are likely to either replace nature as it stands, or, corporations might seek to, overtly or covertly, do away with comparably unreliable biological entities entirely and populate it with synthesised agents. It’s a future that would likely be fragile and fraught with complications, in addition to being devoid of biophilia.

Alamy

AlamyLooking very far ahead, a bio-engineered trajectory for nature could even change our sense of what it means to be human.

Over the past few decades, many have speculated about how we might merge with silicon technology. This technophilic transhumanist view proposes we may eventually integrate with artificial intelligence to enhance human sensory or intellectual capabilities, or ourselves into a digital realm post-death to achieve a kind of immortality.

But what if our path was, instead, to merge with nature? Consider the eco-feminist literature of the late 20th Century, such as in the writings of Donna Haraway, who argued for a “green” transhumanism, where the human integrates with the animal and vegetable in such a way as to be itself transformed. Perhaps the real utility of artificial intelligence is to help us repurpose genes and organisms into, as Haraway puts it, “sympoiesis” – a mutually beneficial hybridisation with humans.

Alamy

AlamyThis post-natural future is far past many people’s comfort zones. It was explored in Jeff VanderMeer’s novel Annihilation (part of the Brave New Weird genre), that became a Netflix film starring Natalie Portman. In the story, a mysterious shimmering zone opens up in the rural US, refracting and splicing DNA between the organisms within it, including that of the soldiers and scientists sent in to investigate. Although elements of both the novel and film engage with concepts of surrender and acceptance to this fundamental merging and co-creation with other life forms, the disruption and multiplication of genetic material is often presented as body-horror, and the motivation of volunteers who enter the zone is explained as self-destructive. Radical change in genomes is conflated with the idea of human identity being completely lost, even while the results on the plants and animals within the zone are sometimes undeniably lovely.

In the far future, consenting adults might welcome a symbiosis with useful augmentations, such as photosynthesising organisms that could be stored in our skin in a way similar to lichen, rather than splice the information from such organisms into our own genome. Or, we might go the whole way and incorporate the genetic information of specific endangered animals into our lineage in perpetuity, in order to become their advocate and information-bearer into the future, as an intimate and protective act.

Netflix

NetflixAll this potential genetic manipulation might feel uncomfortable and strange to many people in the present day. Philosophers, however, have proposed two ways of thinking about the transfer of information which these future trajectories would encom, which I believe will become increasingly important in the post-natural age.

The philosopher Timothy Morton at Rice University argues that we should face not just the beauty but also the darkness and weirdness of nature – an approach he describes as “dark ecology”. He is against separating ourselves from nature by beatifying it, and therefore making ourselves a foreign, estranged and increasingly corrupt influence. Under this viewpoint, ecosystems are in constant change, and climate change is considered a form of “global weirding” that mutates and disrupts nature. Dark Ecology is a way of exploring and accepting both the beauty and horror of humanity’s manipulation of the natural world, much as VanderMeer has portrayed in Annihilation.

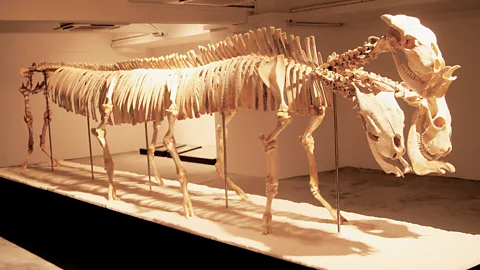

Eli Klein Gallery/Shen Shaomin

Eli Klein Gallery/Shen ShaominIn a similar vein, “process philosophy” considers that there are no real boundaries between humans and the environment, no such thing as an individual, and that all things, including gene flows into the future and their routes, are in a constant state of flux. For example, the cells of our own bodies are the result of symbiosis of two separate microbial lineages in the deep past – a major evolutionary transition discovered by evolutionary biologist Lynn Margulis. What’s more, our genome is littered with the genetic and extra-cellular vestiges of viruses and other parasites, and by adulthood we have more cells in our bodies belonging to other (mainly bacterial) species than of our own. Process philosophy points out that we are inescapably emmeshed with everything and in constant material and informational exchange.

In a far future where bio-technologies have matured, and restrictions on genetic transfer have been removed, we might be able to view a radical change in evolutionary processes from a process philosophy or dark ecology viewpoint. Simply put, a new form of genetic information transfer will have evolved, much like in the major evolutionary transitions of the past.

Center for PostNatural History

Center for PostNatural HistoryRewilding, while currently seeming unlikely, remains the safest and most moral path for the future. But assuming that biotechnology becomes more ubiquitous, it is unclear how exactly we will exist in the post-natural era. Much will be dependent on how we will navigate the unfolding threat of climate change, but if humanity’s long-term trajectory of manipulating nature continues, the future is likely to be a strange land.

The engineered mouse embryos, BioSteel goat, and fluorescent fish at the Center of PostNatural History may just be the beginning. Yet, as Gail Davies, an interdisciplinary researcher at Exeter University, has pointed out, this museum of weird creatures “does not offer a celebration of this technological harnessing of the immanence of life, nor is it a simple rejection. Instead it is a careful exploration of how lives might be lived together.”

--

Lauren Holt is a researcher at the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk at the University of Cambridge. She is exploring the impact of humanity on biological complexity and technology’s effect on ecosystems.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

DEEP CIVILISATION

This article is part of a BBC Future series about the long view of humanity, which aims to stand back from the daily news cycle and widen the lens of our current place in time. Modern society is suffering from “temporal exhaustion”, the sociologist Elise Boulding once said. “If one is mentally out of breath all the time from dealing with the present, there is no energy left for imagining the future,” she wrote.

That’s why the Deep Civilisation season will explore what really matters in the broader arc of human history and what it means for us and our descendants.