How Invisible Man eerily foreshadowed the events of today

Rebecca Hendin

Rebecca HendinIt was a work of its time that speaks powerfully to where we are now, writes Kenneth W Warren.

Although hardly unique in this regard, Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man shows how affirming the capacity of a work to speak to all times (or, at the very least, to our own time) might stand at odds with understanding that work in its own moment.

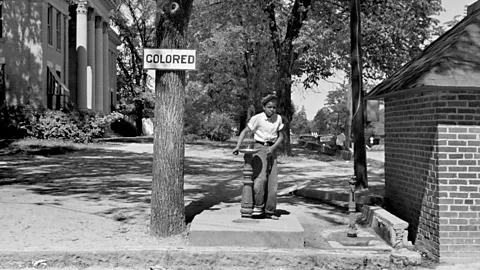

When Ellison’s novel, which chronicled the erratic journey of its unnamed protagonist from the segregated American South to New York City’s Harlem teetering on the brink of social upheaval, appeared in 1952, the United States was still a ‘Jim Crow’ nation. Although the rigour with which the dictates of this regime were enforced varied from time to time and place to place, the society in which Ellison came of age was one where openly discriminatory actions and policies had the sanction of both law and custom. In the years that Ellison wrote his novel, the political and social agitation and decisions in lower court cases that would lead to the US Supreme Court’s landmark ruling in Brown v Board of Education had already signalled that a major social change might be imminent. But the decision itself, which would declare unconstitutional the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’, was still a couple of years off.

Alamy

AlamyAccordingly, Invisible Man took aim at the complex social, psychological and political assumptions and beliefs that enabled those in power to insist (and believe) that relegating the nation’s black population to second-class citizenship was not only compatible with justice but could also be accomplished without inflicting psychic damage on the perpetrators of discrimination themselves. If Invisible Man were to be any kind of novel at all, it would have to take on directly the nation’s moral evasions as they manifested at that moment.

And the task of delineating the specific social types produced by that social system required historical precision. Shortly after learning of the Brown decision, Ellison expressed relief that he’d depicted Dr Bledsoe (the president of the novel’s Negro College, modelled on Tuskegee Institute – now Tuskegee University – who expels Invisible Man’s callow protagonist, thus beginning the young man’s humiliating, if ultimately enlightening, odyssey through the social landscape of black and radical America of the mid-20th Century) before social change had rendered Bledsoe’s social type obsolete. Accepting the demand of social relevance was to risk becoming old news.

Alamy

AlamyOld news, though, is hardly the phrase one associates with Invisible Man these days. It is true that during the 1970s heyday of Black Power and Black Arts, Ellison’s embrace of a Western cultural lineage for his art placed him at odds with many vocal partisans of the Black Aesthetic. Even so, some of his utterances from that period – for example his observation in his essay Society, Morality and the Novel that “it was the existence of human slavery and colonial exploitation which made possible many of the brighter achievements of modern civilisation” – now make him feel quite timely.

That was then, this is now

If Ellison is a Jim Crow author, then he’s a man of our moment, if we are to believe, as Michelle Alexander affirmed in her book, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colour-Blindness, that Jim Crow did not crumble under the assault of the civil rights victories of the 1950s and 1960s, but rather merely went underground. In doing so, it was perhaps like Ellison’s nameless protagonist, disappearing only to resurface in a different guise in the 1980s and 1990s through aggressive, racially targeted policing and sentencing, the goal of which was to reduce much of the US black population to a status verging on, if not identical with, that which blacks experienced from the 1890s through to the 1950s.

Alamy

AlamyThis sense that we are not contending with a new set of social and political circumstances, but are rather, reexperiencing what’s already happened, has become pervasive in some quarters. In late 2011 when I consulted with the Court Theatre in Chicago on its world-premiere adaptation of Invisible Man for the stage, I realised that my role would not be, as is so often the case in adaptations, to figure out how to make this ‘classic’ text relevant to the present. Instead, out of what some might see as a misguided fealty to the concept of historical change, I tried to become a force of defamiliarisation: yes, the world we live in now was powerfully shaped by the society that produced the sensibilities of a writer like Ellison. But it is not a world in which a power-hungry college president can hold sway over a politically silenced black population.

Ellison’s Bledsoe – who the protagonist affirms “was more than just a president of a college. He was a leader, a ‘statesman’ who carried our problems to those above us, even unto the White House; and in days past he had conducted the president himself about the campus. He was our leader and our magic, who kept the endowment high, the fund for scholarships plentiful and publicity moving through the channels of the press” – is no longer a contemporary type. He was a creature of disfranchisement, a political fact that made a mere audience with a US president momentous and the possibility of becoming president sheer fantasy. Our world is not his. Nor is ours a world in which the notion of a ‘black community’, despite the frequency with which the term is used to describe the collective responses and wants of US blacks, can do anything but misrepresent a population that, as pointed out to me recently by the University of Illinois Chicago scholar Cedric Johnson, is larger than the entire nation of Canada.

In many ways, though, Invisible Man itself militates against its own possible obsolescence. Not only does Ellison’s narrator inveigh against those who assert the idea of linear progress or even the possibility that history can spiral upward, warning that “they are preparing a boomerang. Keep a steel helmet handy”, but many of the events that unfold in the novel seem eerily to foreshadow the present. It is virtually impossible to read about Tod Clifton being shot by a police officer for selling paper sambo dolls and not be reminded of the 2014 death of Eric Garner. And the public demonstration organised by the invisible protagonist in protest of Clifton’s death seems a base layer of a palimpsest of innumerable such images that we as readers can now recall.

Alamy

AlamyAll of this is furthered by the iterative structure of the plot in which each demoralising episode experienced by the narrator reveals itself as a version of the attempted dehumanisation of the protagonist that preceded it. The college president and the college ultimately become ‘Brother Jack and the Brotherhood’, thin disguises for the American Communist Party (although Ellison insisted otherwise). It was part of the project of the novel to impugn those who believed that through the proper application of ideology or discipline they could control human behaviour and events, and, accordingly, the plot works to reveal the narrator’s rather tenacious desire to believe the schemes foisted upon him as various forms of blindness.

Yet, for all of its circularity and the fact that the novel ends (and begins) with its protagonist hiding underground in a hole illuminated by 1,369 light bulbs, contemplating a return to the surface where he still might play a socially responsible role, both it and its author, in his various commentaries on novel-writing, remained resolutely optimistic that the US might realise its dream of creating a just and democratic society and that novels could prove to be a useful tool in the process.

Alamy

AlamyThis belief pits Ellison against a prominent strain of thinking that currently prevails among many of the black commentariat. Called ‘Afro-pessimism’, it holds that the very foundation of our idea of human rights and shared humanity depends on the negation of the world’s black people. Where Ellison saw contradiction between ideal and reality, Afro-pessimism sees an inexorable logic in which the very political, economic, and social means that seem most available for achieving a more just world turn out to be nothing more than reasserting a subjugation of a portion of the world’s population.

The point here would not be to find in Ellison’s novel remedies for what currently ails us. Rather, his work might provide a goad for acknowledging and interrogating the material processes and practices that got us from where Ellison was in the early 1950s to where we are now. It’s not that Ellison believed in the possibility of human or societal perfection. Perfection was the delusion of the authoritarian types that people Invisible Man. For Ellison it was quite the contrary.

In his essay on novel-writing, he speculated: “Perhaps the novel evolved in order to deal with man’s growing awareness that behind the facade of social organisations, manners, customs, myths, rituals and religions of the post-Christian era lies chaos”. Ellison believed that “In our time the most articulate form for defining ourselves and for asserting our humanity is in the novel. Certainly it is our most rational art form for dealing with the irrational.” The world was not perfectible, but through art and shared governance it could become profoundly human.

Kenneth W Warren is Fairfax M Cone Distinguished Service Professor at The University of Chicago.

BBC Culture’s Stories that Shaped the World series looks at epic poems, plays and novels from around the globe that have influenced history and changed mindsets. A poll of writers and critics, 100 Stories that Shaped the World, was announced in May.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.