Can art change the world?

Ai Weiwei

Ai WeiweiCan obstruction, or outright destruction, be as powerful as the act of creation? Annie Godfrey Larmon takes a look.

Popular history has it that the word sabotage, from the French sabot, or wooden shoe, was first used in the early 20th Century to describe the labour strike strategy of throwing one’s clogs into machinery to stop up production.

But the word in fact derives from the act of stomping, disruptively, during official speeches. Both origin stories factor into the word’s current use – these are strategies for obstructing systems of power, whether they are economic flows, political events or military operations. This year, the New Museum in New York opened its fourth Triennial, titled Songs for Sabotage, with works by 30-odd artists and collectives from 19 countries that the show’s curators claim set out to “reveal the built systems that construct our reality, images, and truths” with a “call for action, an active engagement, and an interference in political and social structures.” But rather than the documentary images, organisational meetings, and workshops one might expect from such a promise, the show was heavy with paintings and sculptures. Presumably, these works of visual art are, in fact, the songs of the exhibition’s title. Of course, propaganda, allegories, and calls to action are not themselves action, and art that represents change or resistance does not necessarily affect change or resistance.

This brings up a problem that often arises in conversations about art: how can it participate in networks of power that its content willfully rejects? Often, so-called ‘political art’ simply aestheticises protest or resistance. Sometimes, it has the effect of moral licensing – instilling in its viewer a false sense of having accomplished something. Art and power have always been begrudging bedfellows. After all, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels wrote The Communist Manifesto from the comfort of La Maison du Cygne, a gilded restaurant in Brussels.

Ai Weiwei

Ai WeiweiLet’s consider a brief history of sabotage in the art world – in what ways have artists reckoned with the idea that the most powerful acts of creation might be those of destruction? And moreover, if it is possible for artworks themselves to actually interfere in political and social structures, what does that disruption look like? Of course, sabotage isn’t simply about breaking things. Sabotage is breaking things so that something else, something different, can happen.

Appetite for destruction

In of destroying art itself, one might think of Gustave Courbet’s successful proposal, in 1871, to topple and disassemble the Vendôme column during the events of the Paris Commune, a monument he claimed was “devoid of all artistic value, tending to perpetuate by its expression the ideas of war and conquest of the past imperial dynasty.” Or more recently, of British artist Hannah Black’s conversation-fueling but unsuccessful 2017 open letter requesting that Dana Schutz’s painting Open Casket, which reproduced the famous image of Emmett Till at his funeral, be removed from the Whitney Biennial and destroyed. Both of these cases, however, are gestures of framing. The proposals to topple the column and ruin the painting are not artworks in themselves.

Photos-souvenirs: Daniel Buren, March 1969, Bern. Détails. © DB-ADAGP Paris

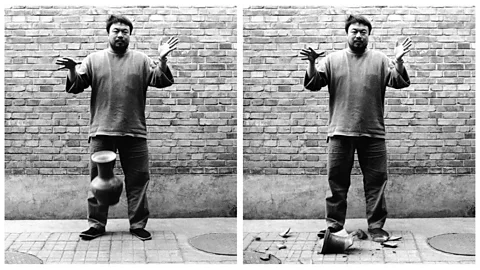

Photos-souvenirs: Daniel Buren, March 1969, Bern. Détails. © DB-ADAGP ParisBy contrast, in 1995, the Chinese artist Ai Weiwei did indeed make an artwork, Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, by destroying another artwork. His performance is represented in three black-and-white photos: the artist holds the 2,000-year-old-ceremonial vase, it is caught in mid-air, it shatters on the floor. By smashing the urn, Weiwei ruins the monetary value of the ancient object, but also its cultural value. And on a symbolic level, the action represents a rejection of the legacies of the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), a defining period in Chinese history. In this way, he provokes the viewer to consider who determines cultural and monetary values alike. But this all plays out only on the level of representation: no political or social system is impeded.

Efforts of art world sabotage are often directed, instead, at the institutions that art, reflecting artists’ frustrations with issues of visibility and accessibility. We might trace this to the 1863 Salon des Refusés, when Courbet, Édouard Manet, James McNeill Whistler and others rejected from the Paris Salon displayed their work, under the auspices of Emperor Napoleon III, in another venue at the Palace of Industry.

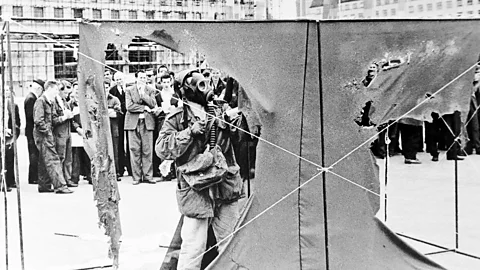

A century later, in 1969, Daniel Buren was excluded from the famous exhibition When Attitudes Become Form in Bern, and in response he covered the city’s billboards with his stripes, effectively inserting himself into the show. He was arrested for this action and had to leave Switzerland. Five years later, the US artist Lynda Benglis responded to misogyny in the art world by paying $3,000 (£2,118) for an ad in Artforum, in which the artist promoted her exhibition at Paula Cooper Gallery in New York by posing naked with a large latex dildo.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesStrategies of withdrawal and refusal have likewise been a mode of art world sabotage. In 1969, the Art Workers Coalition formed, with such artists as Lucy Lippard and Carl Andre at the helm, organising anti-war protests and urging major institutions to close in opposition to the Vietnam War. Their actions were in dialogue with other artist-led organisations at the time, such as Women Students and Artists for Black Art Liberation, directed by Faith Ringgold, and the Ad Hoc Women Artists group, led by Lippard, whose protests resulted in the inclusion of black women artists in the following Whitney Biennial. In 1974, German artist Gustav Metzger attacked the commodification of art through such artworks as The Years Without Art – 1977-1980, which called for a three-year hiatus on all art production, discourse, and sales, though his recruitment process was ill-fated.

Bug in the system

Still other sabotage-like methods galvanise viewers to take action. In a 1968 performance, Argentine artist Graciela Carnevale gathered participants in a glass-fronted gallery in Rosario, Argentina before leaving and locking the door behind her. She hoped to incite “exemplary violence” in the viewers, who were eventually freed by a erby who shattered the gallery door. Tania Bruguera, in 2009, performed Self-Sabotage at Paris’s Jeu de Paume: between readings of her reflections on political art, she took a revolver with a single bullet in its drum, pointed it at her temple, and hazarded the results of Russian roulette. Her action challenged the very efficacy of art to affect reality.

Attempts to fuse art and life full stop have historically been panned by critics – as when the 1993 Whitney Biennial included plumber George Holliday’s home video of Los Angeles police officers beating Rodney King, or when curator Artur Żmijewski invited Occupy Wall Street protesters simply to take over an entire floor of the Seventh Berlin Biennale in 2012.

Graciela Carnevale/Spai Visor

Graciela Carnevale/Spai VisorThese projects sabotage the very concept of what an artwork can and should be. But to return to the opening question: what artworks actually do serve to interfere with political and social structures? Hard-pressed, I can think of only a handful that supersede the fraught dynamics of art, life, and power to intervene in systems while maintaining rigor in form or concept – works of art that actually do have purpose and effect on the real world.

Twitter/ does not wish to be identified

Twitter/ does not wish to be identifiedIn 1997, the German artist Christoph Schlingensief pulled off one such work when he organised Tötet Helmut Kohl! (Kill Helmut Kohl!), for which he gathered as many unemployed people as possible to swim in then-German chancellor Helmut Kohl’s favourite holiday destination, the Austrian Wolfgangsee, while the politician was on holiday. He claimed that all of ’s unemployed would together displace the lake’s water. In 2014, Lawrence Abu Hamdan made the work The All-Hearing, for which he asked two sheikhs in Cairo not to deliver their usual weekly Friday sermons, but instead to deliver city-wide speeches about the dangers of noise pollution as a public health issue. Schlingensief and Abu Hamdan alike disrupted a status quo to force a change.

Ivan Kafka/Artlist.cz

Ivan Kafka/Artlist.czOf course, sabotage is mischievous. Often, it is an intervention that begins as a minor interference that multiplies or magnifies to result in the destruction of a system. And often, it is perpetrated anonymously. This relationship to duration and authorlessness alone makes true sabotage an irksome task for artists. That said, my favourite act of artistic sabotage was perpetrated in 1981, in the quiet of the night, by Czech artist Ivan Kafka. Overnight, in the cobblestones of Jansky Street in Prague's Neruda district, just below the castle that serves as the historical and symbolic head of the Czech government, Kafka arranged 1,000 wooden sticks that stood upright. When local residents opened their doors to leave for work in the morning, they were faced with the decision to trample the work – then an illegal act of free expression – or to preserve it and fail to appear for their jobs. Kafka’s installation brings to mind a line from scholars Fabio Rambelli and Eric Reinders: “Destruction is not the end of culture but one of the conditions of its possibility.”

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.