'It will be a great hoax in the history of mankind': How fake Hitler diaries fooled the British press

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn April 1983, a German magazine, Stern, and a British newspaper, The Sunday Times, claimed to have made one of the century's most extraordinary historical discoveries. In fact, it was one of the century's most extraordinary hoaxes – and the scandal that followed cost millions and ruined reputations.

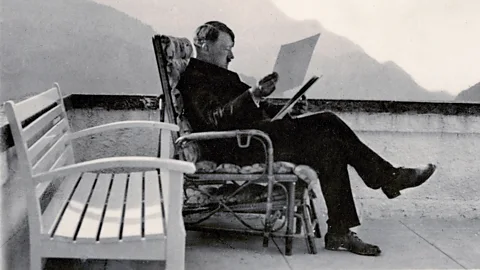

On 25 April 1983, 42 years ago this week, respected German magazine Stern published what they believed to be the most spectacular historical scoop: the previously unknown private diaries of Adolf Hitler. To show off their extraordinary exclusive to the world's press, the weekly news magazine had arranged a Hamburg press conference for the same day. The story would indeed dominate global headlines – but not in the way the magazine hoped.

Three days earlier, Stern's London editor Peter Wickman had told BBC News that they were "absolutely convinced" that they had the authentic Hitler diaries in their hands. "We were very dubious at the beginning, but we had a graphologist looking at them, we had an expert who compared the paper. We had historians like Professor Trevor-Roper, and they are all convinced they are genuine."

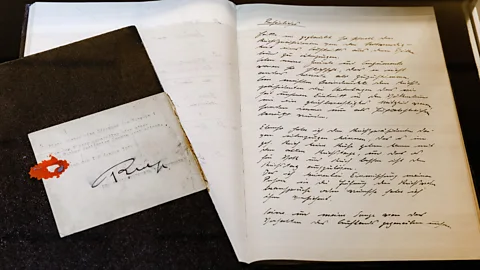

The handwritten journals ran from 1932 to 1945, covering the entire period of Hitler's Third Reich. "There are 60 diaries, they look a bit like school exercise books but with a hard cover. They have seals outside with a swastika and an eagle and inside, of course, Hitler's very spidery gothic handwriting," Wickman told the BBC.

Stern believed that their discovery had the potential to rewrite what was previously known about the Nazi leader. And the diaries' content was certainly eye-opening, revealing a little-known sensitive side to the Führer. They detailed everything from Hitler's battles with flatulence and halitosis, and the pressure from his girlfriend Eva Braun to get Olympics tickets, to notes about sending Stalin – "the old fox" – a birthday telegram. The notebooks also seemed to indicate, somewhat startlingly, that the Nazi leader was unaware of the Holocaust that was being carried out in his name.

The journals had supposedly been unearthed by Stern journalist Gerd Heidemann. The reporter was already regarded around Stern as something of a Nazi memorabilia obsessive. In 1973, the magazine had assigned him to write a story about a dilapidated yacht which had once belonged to Hitler's second-in-command, Hermann Göring. Heidemann spent a fortune buying the yacht and restoring it. He also began an affair with Göring's daughter Edda, who introduced him to a number of former Nazis. It was through these s, Heidemann said, that he had come across Hitler's diaries.

Alamy

AlamyHeidemann claimed that the plane had been carrying the diaries, which were salvaged from the crash and stowed away in a hayloft. In the intervening years, they had found their way to an East German collector who was now offering to sell them. The reporter would negotiate the deal to buy them, acting as intermediary between his East German source and Stern.

The promise of a sensational world exclusive, providing previously unknown insight into the mind of the Nazi dictator, proved irresistible to the magazine. But Stern was determined to keep a tight grip on who knew about their scoop, so when they hired handwriting experts to authenticate the diaries – providing them with "genuine" Hitler documents for comparison – they would only give them a few selected pages of the notebooks to look at. Stern ultimately forked out some 9.3 million Deutschmarks (£2.3m) for the volumes, and, having paid such an exorbitant sum, opted to store them in a Swiss vault for safekeeping.

The first historian to examine the diaries was Prof Hugh Trevor-Roper, also known as Lord Dacre of Glanton. In 1947, he had written a book, The Last Days of Hitler, which had brought him a great deal of academic prestige, and he was regarded as a leading expert on the Nazi dictator. He was also an independent director of The Times newspaper, which two years earlier had been acquired along with its sister paper, The Sunday Times, by Rupert Murdoch.

Lord Dacre was initially sceptical about the diaries, but flew to Switzerland to view them. His opinion began to be swayed when he heard the diaries' origin story and was told, erroneously, that chemical tests had found them to be pre-war. But what really tipped the balance for the historian was seeing the huge volume of material involved.

"The thing that struck Hugh Trevor-Roper most forcefully and certainly struck me as a non-expert when I saw the original material was the sheer scale of it," The Times editor Charles Douglas-Home told the BBC on 22 April 1983. "The enormous range of this archive. It's not just that there are nearly 60 volumes of notebooks filled out in Hitler's longhand which is there, there are about 300 of his drawings and pictures and personal documents such as his party card. I there are the drawings which he submitted to art school when he was a young man hoping to get into art school, and there is a painting, an oil painting and so on. Now a forger would have to be very good to forge across that whole range."