Orlando: The most subversive history film ever made

Alamy

AlamySally Potter's adaptation of Virginia Woolf's classic novel – the film marking its 30th anniversary this year – starred Tilda Swinton as a time-travelling, sex-changing figure. It was a transgressive riposte to the homophobia of early-90s Britain, and remains relevant today, writes Rachel Pronger.

Orlando is a book that inspires devotion. Virginia Woolf's experimental novel was an immediate critical and commercial success when it was first published in 1928, and its reputation has only grown since. The story of a time-travelling aristocrat who lives through 400 years of history – and changes sex along the way – Orlando was originally written as a tribute to Woolf's lover Vita Sackville-West, and is now celebrated as a queer and feminist landmark. It has inspired generations of artists, filmmakers and writers, and been reimagined as ballet, opera and theatre – the latest stage version opens in London this autumn.

More like this:

- The only surviving recording of Virginia Woolf

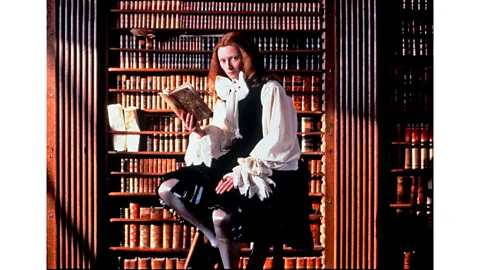

The best of these retellings approach Orlando as an ever-evolving work of queer imagination. Sally Potter's film adaptation, which marks its 30th anniversary this year, is a case in point. Warmly received upon its Venice Film Festival premiere in 1992, Potter's Orlando is now considered a bravura work of adaptation. Starring Tilda Swinton in the title role, the film is a historical romp full of wit and sumptuous detail. Yet despite the era-spanning narrative, it's also a film that reflects a very specific moment in British history. True to the spirit of Woolf's text, Potter's Orlando is steeped in queer culture, and has become over the decades a subject of fascination – and ambivalence – for successive generations of LGBTQI+ fans.

It took Potter almost a decade to bring Orlando to the screen. The filmmaker first fell in love with the book as a teenager, immediately recognising its cinematic potential. "When I read it, I could see it," Potter has said. "I experienced it… as a series of images hurtling through time and space from 1600 to the present day." She began pitching Orlando to funders in 1984, but was told that the concept was "unmakeable, impossible, far too expensive and anyway not interesting." Potter was temporarily discouraged, but in the late-1980s she returned to the project with renewed determination.

Alamy

AlamyAdapting Woolf's amorphous text was a challenge. In a 1993 interview, Potter described how she initially worked methodically – "reading, re-reading and reading again" – before putting the novel aside, and treating the script "as something in its own right, as if the book never existed." The resulting screenplay captures Woolf's anarchic spirit but makes bold adjustments to facilitate the translation to a new art form. The book's addresses to the reader for instance, are reflected by Orlando's playful breaking of the fourth wall. In one memorable scene, Orlando wakes from a long sleep to discover they are now in a woman's body. "Same person, no difference at all," says a naked Swinton, looking directly down the camera lens. "Just a different sex."

Potter also made significant plot changes. Woolf does not explain Orlando's immortality, but in the film it is implied that this longevity has been gifted by Queen Elizabeth (Quentin Crisp) who, infatuated by Orlando's beauty, insists they must stay young: "do not fade, do not wither, do not grow old." Potter also offers a bittersweet change to the ending by having the protagonist give birth to a daughter rather than a son, resulting in the loss of Orlando's inheritance. This change reflects more accurately the real life of Sackville-West, who as a woman was barred from inheriting her ancestral home of Knole. These adjustments serve to draw out the novel's queer and feminist subtext, and in doing so they also suggest ways in which the film was shaped by the era in which it was made.

'A contradictory moment'

Potter began making films in the 1980s as part of a radical artistic scene working in response to the neoconservatism of Margaret Thatcher's Britain. Section 28, which prohibited the "promotion of homosexuality" by local authorities, was introduced in 1988, against the backdrop of the escalating Aids crisis. Filmmakers such as Derek Jarman reacted to this heightened homophobia by making outspoken work centring queer politics, boundary-pushing films that found a home on television on the newly launched Channel 4.

As the writer So Mayer explains, this was a contradictory moment. "What's happening in the early 1990s is the crest of a wave that starts in the squats and protests of the 1970s," Mayer tells BBC Culture. "Queer experimental art was being made in the face of institutionalised and culturally prevalent homophobia. Orlando's conceptualisation starts in the heart of neoliberalism and Thatcherite destruction." With its luscious historical imagery, Potter's film might look like an escapist fantasy, but it is littered with topical references to this very specific socio-political moment.

Although it does not offer explicit political critique, Orlando radically centres queer culture, and is full of references that speak to LGBTQI+ viewers across the generations. By casting an 83-year-old Quentin Crisp as Queen Elizabeth I, Potter pays tribute to a gay icon while adding another layer to the film's discussion of identity. Described by Potter as "the Queen of Queens," Crisp would go on to identify as transgender and use she/her pronouns in the final years of her life. Rewatching the film with this knowledge adds a dimension to the film's reflections on the mutability of gender.

Elsewhere, a recurring cameo from musician and activist Jimmy Somerville gestures towards a younger generation. Somerville first appears as a Tudor countertenor in the film's opening scenes before popping up again across each of the film's eras. A final surreal appearance at the film's conclusion – in which Somerville stars as a tinfoil-clad angel singing in the sky – seems to reference the Aids crisis, which at that moment was having a devastating effect on the queer artistic community within which Potter was working.

One high-profile victim was Derek Jarman, who would die of Aids-related illnesses in 1994. Although not directly involved in Orlando, Jarman was an important influence. Potter and Jarman had first become friends in the mid-1980s when visiting the then-Soviet Union as part of a delegation of independent filmmakers. "As the only gay male and the only female directors in the group we became natural allies," Potter ed. Jarman publicly advocated for Potter as she struggled to get Orlando made, and the film is indebted to Jarman's iconoclastic approach to period drama, as seen in Caravaggio (1986) and Edward II (1991). Potter also recruited several Jarman collaborators, most notably Swinton, and the costume designer Sandy Powell. In Orlando, Potter draws upon Jarman's pioneering "queering" of the historical genre, and in doing so furthers a legacy that has been continued in recent subversive period pieces such as The Favourite.

An enduring message

Given these ties to queer culture, it's unsurprising that Orlando often provokes strong reactions in LGBTQI+ viewers. Mayer has written a book on Potter and is currently working on a monograph about Orlando. They vividly the first time that they saw the film as teenagers in 1993. "My friends hated it, and wanted to leave; I was enrapt and wouldn't," recalls Mayer. "So my first memory of watching the film is having a furious row in whispers with my then-best friends, who walked off after the screening." Years later, Mayer realised that part of the film's appeal was its queerness. "It had given me a window into something that I had only glimpsed through [long-running BBC pop music programme] Top of the Pops… In some ways, I understood that I loved it for the same reasons that my friends hated it, and that they were reasons, both aesthetic and political, that I couldn't articulate."

Alamy

AlamyOrlando's unpindownable quality has often provoked debate. Greater awareness of Woolf's queerness has added to this discussion, as has our evolving understanding of gender identity. Is Orlando, as Jeanette Winterson has argued, "the first English-language trans novel">window._taboola = window._taboola || []; _taboola.push({ mode: 'alternating-thumbnails-a', container: 'taboola-below-article', placement: 'Below Article', target_type: 'mix' });