Kahlo and Vermeer: What courage really means

Wikimedia

WikimediaFrom the concealed suffering of Sandro Botticelli’s Fortitude to Frida Kahlo’s serene gaze, Kelly Grovier explores a history of artworks showing bravery.

“Courage,” the pioneering French artist Henri Matisse once insisted, “is essential to the artist, who has to look at everything as though he were seeing it for the first time.” If we are to believe the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, who died in 1860 (nine years before Matisse was born), courage isn’t only necessary in order to create; it is likewise required to see, feel, and appreciate a work of art, which alone offers humankind the opportunity to rise above the petty and soul-destroying distractions of this world.

Only when we allow ourselves to dissolve into the contemplation of a work composed for eye or ear, Schopenhauer believed, do our ruinous attachments to the here-and-now evaporate. When immersed in the intensities of pigment or sound, he argued, we are “snatched out of that eternal flux of all things and removed into a dead and silent eternity”. Truly to connect with a painting, sculpture or musical composition, therefore, requires fortitude and a brave willingness to cease being altogether (‘dead and silent’) and to acquiesce entirely to the pulse and rhythm of a work that holds us in its thrumming thrall.

Schopenhauer may not have been beleaguered by the same infuriating forces of fake news and alternative facts that beset our own post-truth world, but he was no stranger to turbulent times. Born the year before the French Revolution kicked off, he lived to witness a wearying succession of wars and political storms throughout the first half of the 19th Century. To his eye, it was the masters of the 16th- and 17th-Century Dutch Golden age (artists such as Frans Hals, Rembrandt, and Jacob van Ruisdael) who succeeded most in ‘snatching’ an observer out of the fleeting skirmishes of the era into a deeper mindfulness of what it meant to be alive.

Wikimedia

WikimediaThe poetic perseverance of the woman who watches milk pour from the jug she tilts for eternity in Johannes Vermeer’s The Milkmaid (c 1658), as if measuring the flow of days and years that empty from the vessels of our own existences, is as fearless as it is formidably beautiful. She’s the engine in a perpetual circuit of strength: the courage it takes to succumb completely to her courage fortifies our own fortitude. Her endurance helps us endure.

The calm of the storm

The sweet serenities of Vermeer’s much-adored metaphorical interiors (from Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window (c 1657) to The Allegory of Painting (1666), from The Lacemaker (1670) to Lady Seated at a Virginal (c 1672)) offer themselves as life lessons in how to become one with the world’s mysterious weave of shadow and substance. Centuries before the Dutch master’s succession of symbolic figures, the Early Renaissance genius Sandro Botticelli sought to establish his own reputation by demonstrating a finesse in personifying the feeling of courage. Among the earliest known works by the future creator of The Birth of Venus, Botticelli’s Fortitude (painted in 1470, when the artist was in his early 20s) is a case study in psychological tensions capable of enrapturing the viewer.

Wikimedia

WikimediaThe work is the only contribution that the young Botticelli would make to a cycle of seven representations of Virtues that adorned the Tribunal Hall of Piazza della Signoria in Florence (the other six issuing from the workshop of the noted Florentine painter Piero del Pollaiolo.) What distinguishes Botticelli’s , however, is the intensity of emotion that he manages to enkindle beneath Fortitude’s deceptively placid countenance. The aspiring artist isn’t content to allow the stock props of ceremonial sceptre, militaristic armour and bejewelled breastplate determine the work’s meaning as an unambiguous embodiment of bravery. Trouble has packed the bags that weigh down Fortitude’s eyes. Her soulful, sidelong gaze pulls us into its orbit of concealed suffering and whatever anguish she has stoically overcome. Courage is commendable, but that doesn’t mean that it is easy to muster or that its conscience is clear.

Wikimedia

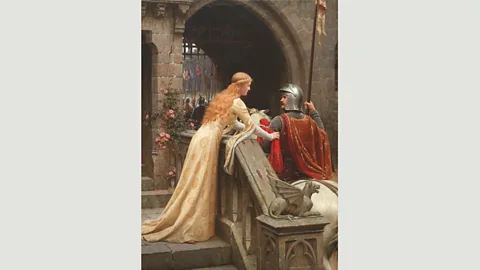

WikimediaFrom Botticelli’s day to our own, only those profiles in courage that, like his poplar portrait, candidly confess to the emotional complexities of what bravery truly entails will endure in cultural consciousness. Psychologically saccharine works, such as Edmund Leighton’s sentimental God Speed (1900), haven’t the intensity of insight or authenticity of feeling necessary to hold our attention decade after decade, age after age. Leighton’s painting is technically proficient in imagining the departure of a knight into battle – the crispness of sculptural form (one can almost touch its growling stone griffin, an emblem of battlefield valour) and the exquisite flow of lush fabrics. Yet the work’s human intelligence is naff – as thin and flimsy as the linen canvas on which it’s painted.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAlmost half a century later, Mexican serial self-portraitist Frida Kahlo showed the art world what courage really looked like with a mesmerising work that was as mysterious as it was powerful. At first blush, Kahlo’s beguiling Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird (1940) might seem more a study in star-crossed superstitions and luckless portent than in heroic resolve. The artist presents herself as almost hopelessly hemmed in by misfortune. She literally has a monkey on her back who casually tightens a choker, whose sharp and painful spikes dig into her neck, drawing blood.

Meanwhile, an ominous black cat shadows the artist (perhaps a symbol of the pain that followed ever since her spine was crushed in a bus accident in 1925, when she was 18), while blocking the transcendent trajectory of a pair of butterflies above her head are a brace of dragonfly-like insects (the ‘devils needles’ in indigenous folklore, capable of sewing up the lips of children) – a particularly stinging allusion given the artist’s inability to have children. Yet through it all, a serene self-possession vibrates unmistakably from the artist’s eyes, which gaze out at us with an otherworldly calm. It is almost as if Kahlo is holding a wild card of deep internal courage that she knows can trump any tragedy this world can deal her.

Wikimedia

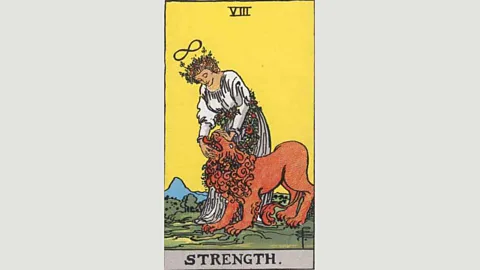

WikimediaLook closer at the composition of the work and one begins to recognise a profound similarity between its assembly of symbols and those of the ‘Strength’ card in the Major Arcana picture trumps of the tarot deck. Traditionally known as ‘Fortitude’, the Strength card depicts a woman also surrounded by foliage and accompanied by a fearsome feline she fearlessly tames. Above her head floats a sinuous infinity symbol.

This harmonious geometric halo, which keeps ‘Strength’ tethered to the endless energies of eternity, is a mystical accessory shared too by Kahlo, who has woven a subliminal semblance of the ancient shape from purple cloth into her hair. Unlike Leighton, Kahlo hasn’t attempted to isolate fortitude as a smugly righteous property removed from anguish and fear, but has entangled it into the complex tapestry of a life punctuated by pain. In so doing, she has created a far more entrancing work that repays meditation – a canvas worthy of our own courageous leap into the ‘dead and silent eternity’.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.